Peter Righton’s writing on child abuse in Child Care: Concerns and Conflicts – his cynical exploitation of a post-Cleveland situation

Posted: August 28, 2015 Filed under: Abuse, PIE | Tags: butler-sloss, cleveland child sexual abuse scandal, geoffrey wyatt, marietta higgs, paedophile information exchange, peter righton, richard alston, sonia morgan 1 CommentIn light of the conviction yesterday of Peter Righton‘s lover Richard Alston on child abuse charges, in which information was brought to the court’s attention about Alston and Righton abusing a boy together, I intend to update my blog posts on Righton (who was on the executive committee of the Paedophile Information Exchange, and wrote openly about paedophilia) to include more information about Alston, which I previous omitted as he was still awaiting trial which I would not have wished to prejudice. I also plan to blog some more information specific to Alston. But here is another essay from Righton which I am blogging here for the first time.

Peter Righton in 1992.

In 1976 Righton co-edited with Sonia Morgan a collection of essays entitled Child Care: Concerns and Conflicts (London: Hodder Education, 1989), a revised edition of which appeared in 1989, for which Righton also wrote an introduction, which I have reproduced below.

In this introduction, Righton writes first on the family, which he portrays primarily as a site of conflict and tension in light of increasing rates of divorce, remarriage and single-parent families, and advocates a greater degree of sharing of care responsibilities between families and agencies in such situations. It is not difficult to see how this constitutes a strategy on the part of Righton and other paedophiles to increase the availability of deeply vulnerable children for exploitation.

Then Righton includes a section on Child Abuse (following a brief mention of it in the section on the family). Whilst at first he is very keen to stress how the majority of child abuse occurs in the family (which while true is something often flagged up by non-familial paedophiles to take the attention of them), and then draws attention to the 1987 Cleveland Child Sexual Abuse Case, in which 121 diagnoses were made during a five month period leading to children being taken away from their parents and placed in care or hospital on grounds of suspected abuse. The subsequent inquiry, chaired by Lord Justice Butler-Sloss, concluded that most of the diagnoses were inaccurate, and most of the children were returned to their parents. Righton cites this case in order to highlight the danger of false allegations, and goes on (in a manner which is most familiar from PIE and other paedophile publications) to argue that the damage done to children by investigations by social workers and others can be as great or greater than the damage of abuse itself. Righton evokes the idea of a boy or girl who ‘has denied that he or she has been subject to molestation by a parent, yet knows that denial is not believed’, as if this were the primary form of disbelief about which one should be worried.

I do not intend here to express a view on the validity or otherwise of the particular reflex anal dilation test which (nor am I in any sense qualified to do so) by Dr Marietta Higgs and Dr Geoffrey Wyatt. But I offer this to show just quite how cynically a paedophile like Righton could snap up any chance available to portray over-zealous social workers intervening in cases of suspected child abuse. Ultimately, what Righton wanted was least intrusion as he and his networks continued to abuse children in the most hideous manner. That he was able to obtain a position of such respect in the social work profession, and use this to propagate his insidious propaganda, is deeply disturbing.

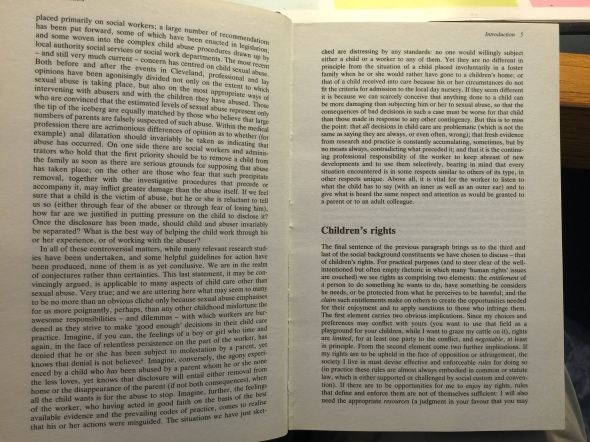

From the memoirs of John Henniker-Major, 8th Baron Henniker (1916-2004)

Posted: March 3, 2015 Filed under: Abuse, History, Islington, NCCL, PIE | Tags: charles napier, charlotte russell, islington, john henniker-major, lord henniker, national council for civil liberties, paedophile information exchange, peter righton, pie, thornham magna 4 CommentsBelow I reproduce some sections from the volume Painful Extractions: Looking back at a personal journey (Eye: Thornham Books, 2002) by John Henniker-Major, the 8th Baron Henniker. Henniker is of interest to those investigating organised child sexual abuse because of the fact that the notorious Peter Righton, former Executive Committee member of the Paedophile Information Exchange, author of various freely available writings advocating sex with children, and senior figure in the social work profession, took up residence on Henniker’s estate, Thornham Magna, following Righton’s conviction for importing and possessing pornographic material featuring children in 1992. Numerous groups of children were brought from Islington and elsewhere to Thornham Magna on day trips and it is feared that they were the victims of abuse at the hands of Righton; the Exaro website has cited one person alleging brutal sexual assault and violence from Righton, also involving the former PIE treasurer Charles Napier, recently jailed for 13 years for sexual offences against 23 boys, and now even a sadistic murder by Righton on the estate.

I hope to be able to post a more comprehensive guest blog post on Henniker and his relationship to disgraced former diplomat Peter Hayman soon.

When time permits, I intend to thoroughly update my blog post on Righton to take account of the amazing research collected on the blog of Charlotte Russell, drawing upon a wide range of previously unseen archival documents. I cannot recommend strongly enough that anyone interested in particular in the Paedophile Information Exchange, and its links to the National Council of Civil Liberties and to politicians therein, read the various meticulously researched posts on this blog.

More pro-child sexual abuse propaganda from Germaine Greer

Posted: November 12, 2014 Filed under: Abuse, NCCL, PIE | Tags: city of london school for girls, germaine greer, helen goddard, paedophile information exchange, tom o'carroll 6 CommentsIn an earlier post I drew attention to the justifications for sexual abuse of children provided by Germaine Greer, in particular in the case of Helen Goddard, convicted abuser who taught at City of London School for Girls. I have just come across a quote from considerably earlier, from a 33-year old Greer. Clearly this type of view has been consistent throughout her career; I believe all of her writings and work in other media should be more closely scrutinised in light of this.

One woman I know enjoyed sex with an uncle all through her childhood, and never realized that anything unusual was toward until she went away to school. What disturbed her then was not what her uncle had done but the attitude of her teachers and the school psychiatrist. They assumed that she must have been traumatized and disgusted and therefore in need of very special help. In order to capitulate to their expectations, she began to fake symptoms that she did not feel, until at length she began to feel truly guilty about not having been guilty. She ended up judging herself very harshly for this innate lechery.

Germaine Greer, ‘Seduction is a Four-Letter Word’, Playboy (January 1972), p. 82, cited in Richard Parson, Birthrights (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974), p. 151.

It is not surprising that Tom O’Carroll, former chair of the Paedophile Information Exchange, should have been so enamoured of Greer (see his comments on her in ‘Is PIE Sexist?’, Magpie 12 (December 1978)) , and continued to enthusiastically report her support for Harriet Harman and NCCL this year; according to O’Carroll Greer argued on Any Questions? ‘that the age of consent issue was not just about paedophiles but about young people’s right to a sexual life, which was why she and others had supported changing the law’.

Michelle Elliott, researcher into sexual abuse committed by women, in the interview below (from about 9’25”) quotes Greer’s comment to her ‘Well, if it is a woman having sex with a young teenage boy, i.e. 13 or 14-year-old, and he gets an erection, then clearly it’s his responsibility’.

Be very sceptical about online communications laws which protect the powerful – social media and the right to offend

Posted: October 20, 2014 Filed under: Abuse, Conservative Party, History, Labour Party, Liberal Democrats, Politics, Westminster | Tags: alan dershowitz, angela merkel, cecil parkinson, censorship, chris grayling, david k. nelson, david mellor, edwina currie, eric joyce, fiona woolf, freedom of speech, george galloway, gerald scarfe, harold washington, harold wilson, harriet harman, home affairs select committee, israel, latuff, lindon baines johnson, malicious communications act, margaret thatcher, mark reckless, mark rowson, martin rowson, napoleon, paedophile information exchange, palestine, peter morrison, richard newton, robert walpole, sarah ferguson, simon danczuk, stella creasy, steve bell, tony blair 4 CommentsToday the UK Justice Secretary, Chris Grayling, clarified that what he called ‘a baying cyber-mob’ could face up to two years in jail under new laws. This refers to proposed amendments to the 1988 Malicious Communications Act, to quadruple the maximum sentence. Already, as modified in 2001 (modifications indicated), the law defines the following offence:

1. Offence of sending letters etc. with intent to cause distress or anxiety

Any person who sends to another person—

(a)a [F1 letter, electronic communication or article of any description] which conveys—

(i)a message which is indecent or grossly offensive;

(ii)a threat; or

(iii)information which is false and known or believed to be false by the sender; or

(b)any [F2 article or electronic communication] which is, in whole or part, of an indecent or grossly offensive nature,

is guilty of an offence if his purpose, or one of his purposes, in sending it is that it should, so far as falling within paragraph (a) or (b) above, cause distress or anxiety to the recipient or to any other person to whom he intends that it or its contents or nature should be communicated.

(2)A person is not guilty of an offence by virtue of subsection (1)(a)(ii) above if he shows—

(a)that the threat was used to reinforce a demand [F3 made by him on reasonable grounds]; and

(b)that he believed [F4, and had reasonable grounds for believing,] that the use of the threat was a proper means of reinforcing the demand.

[F5 (2A)In this section “electronic communication” includes—

(a)any oral or other communication by means of a telecommunication system (within the meaning of the Telecommunications Act 1984 (c. 12)); and

(b)any communication (however sent) that is in electronic form.]

(3)In this section references to sending include references to delivering [F6 or transmitting] and to causing to be sent [F7, delivered or transmitted] and “sender” shall be construed accordingly.

(4)A person guilty of an offence under this section shall be liable on summary conviction to [F8 imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months or to a fine not exceeding level 5 on the standard scale, or to both].

Under the new amendments, the maximum sentence would be two years.

Direct physical or other threats are indeed a worrying phenomenon of social media, as are any threats to politicians or others in public life, and I have no problem with these being criminalised. But it is clear that this law goes much further than that. In particular, the terms ‘indecent’ and ‘grossly offensive’ are very nebulous, and could be used in highly censorious ways, as I will attempt to demonstrate presently.

Amongst those cited in support of Grayling’s laws are former Conservative MP Edwina Currie and Labour MP Stella Creasy. A 33-year old man, Peter Nunn, received an 18-month sentence for abusive Twitter messages against Creasy. Yet Creasy’s rank hypocrisy was amply demonstrated when challenged by myself and various others some weeks ago to condemn a case where violence was not merely threatened but actually carried out, in a frenzied attack against Respect MP George Galloway by Neil Masterson, who appears to be a neo-fascist supporter of the Israeli government. The 60-year old Galloway was leaped on in a frenzied manner by the attacker, and suffered a broken jaw, suspected broken rib and severe bruising to the head and face through the attack. There were a shocking number of people posting online in many places to say Galloway deserved it.

Just a few prominent commentators made an issue of this. Peter Oborne, writing in the Telegraph, drew attention to the fact that no political party leader, nor the Speaker of the House of Commons, had condemned this attack on Galloway, which Oborne called ‘beyond doubt an attack on British democracy itself’. He added:

Had an MP been attacked by some pro-Palestinian fanatic for his support of Israel, I guess there would have been a national outcry and rightly so. Why then the silence from the mainstream establishment following this latest outrageous assault on a British politician?

Times journalist Hugo Rifkind, no political supporter of Galloway, tweeted on 31/8 ‘What happened to @georgegalloway shouldn’t happen to any politician in this country. Horrifying. Hope he’s okay.’

Amongst the responses were one by @77annfield, who said ‘any physical attack is wrong but it was his personality that brought it on’ (i.e. he basically deserved it), a few days later by an @ElectroPig who said ‘It shouldn’t happen to an HONEST politician who actually gives a damn. The rest of the bastards? #FineByMe’.

No UK party leader nor prominent politician condemned this attack on a fellow MP. Can we presume that Creasy thinks physical assault is OK, or at least not much of an issue, when it is against a political opponent or someone she doesn’t like? I am quite sure that if Creasy had suffered such an attack, and had her jaw and ribs broken, Galloway would have wholeheartedly condemned it.

Edwina Currie is currently the subject of various scrutiny for her role in appointing Jimmy Savile to a taskforce to run Broadmoor prison,, where he was involved in widespread sexual abuse, and also for the fact that she knew about the paedophile activities of late Conservative MP Peter Morrison, but appeared to do nothing about it until she could use it in diaries she had to sell. She said on the subject of Grayling’s proposals:

Most people know the difference between saying something nice and saying something nasty, saying something to support, which is wonderful when you get that on Twitter, and saying something to wound which is very cruel and very offensive.

it should not be surprising if Currie only wants ‘nice’ things said about her, considering her record. But the freedom to say things which are cruel, very offensive, and may be designed to wound, is fundamental in a democracy, I would say, however much Currie may not wish it to be. I worry about the implications of this law more widely to be possibilities of political dissent and satire in an age in which electronic communications and social media play a more prominent role than ever.

With this in mind, I would strongly recommend watching the two part 1994 BBC series written and presented by Kenneth Baker (now Lord Baker), From Walpole’s Bottom to Major’s Underpants, tracing the history of the political cartoon.

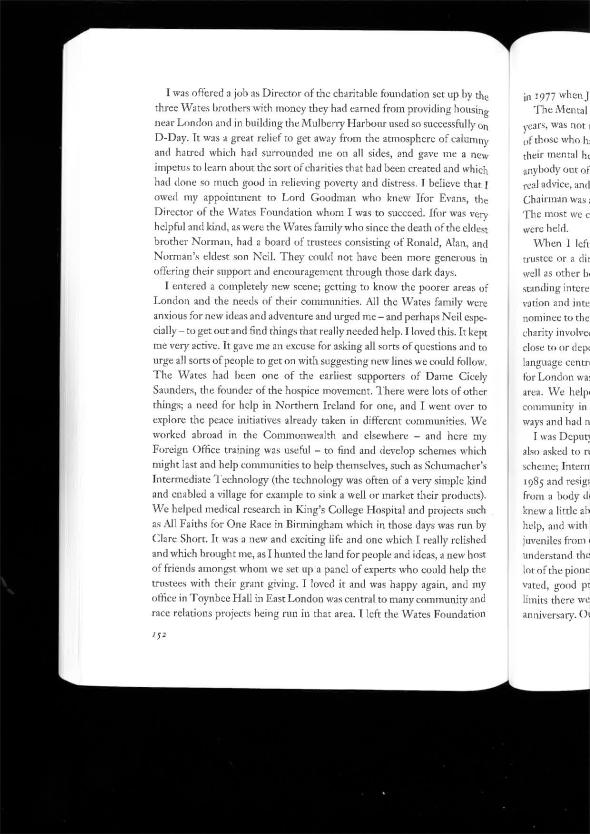

The image below, produced anonymously in 1740, refers to Robert Walpole, Prime Minister from 1721 to 1742.

This dates from 1797, and is by Richard Newton, showing Pope Pius VI kissing the bare bottom of Napoléon Bonaparte.

More recently, this image from 1967, drawn by Gerald Scarfe for Private Eye, shows Harold Wilson pulling down the back of Lindon Baines Johnson’s trousers and pants, as a comment on the Vietnam War; the original image actually had Wilson’s tongue up Johnson’s bottom, but then-editor Richard Ingrams thought this was too much.

This 1988 image, Mirth and Girth by then School or Art Institute of Chicago student David K. Nelson Jr, is of former Chicago major Harold Washington. This picture was confiscated by Chicago police, though Nelson later won a federal lawsuit against the city on the grounds of the confiscation and damage to his picture.

This from 2006, by cartoonist Latuff, shows fundamentalist pro-Israel zealot Alan Dershowitz masturbating over the sight of carnage in Lebanon brought about through Israeli military action.

This cartoon from Martin Rowson from 2007 at the time of Tony Blair’s resignation as Prime Minister, hardly hides its ‘fuck off and die’ message.

And here, from 2012, is a Steve Bell cartoon portraying Angela Merkel as a dominatrix of Europe.

Other example would include a bare-breasted Margaret Thatcher on Spitting Image (which I have been unable to find to post here), and countless other images from that programme (look at the treatment of Cecil Parkinson, David Mellor or Sarah Ferguson, for example, after all were embroiled in sex scandals).

All of these could be more than plausibly described as ‘indecent’ (except perhaps the Rowson cartoon) and ‘grossly offensive’. They all appeared in mainstream publications, but what would happen if a cartoonist posted them online, and tweeted them, perhaps with the hashtag of their subjects included? If they would be liable for prosecution and possibly a two-year prison sentence, this would be an extremely worrying development indeed.

I have seen and experienced intimidation online by other pro-Israeli neo-fascists, who spread messages of sometimes violent hatred. Some students have been revealed to have been paid by the Israeli government to act as propagandists, and I would imagine some of the people I have encountered are amongst these. I cannot imagine these laws being used against them (and certainly have not heard of such a case), though in the future I could certainly imagined them being used to intimidate pro-Palestinian campaigners, by branding various views they might express (such as, for example, that the foundation of the state of Israel involved the dispossession and ethnic cleansing of Palestinians, and cannot be accepted as legitimate) as ‘anti-semitic’, and as such constituting quasi-hate crimes against those to whom they are addressed. In neither of these cases is criminalisation appropriate.

In the UK, there is no written constitution as such, and thus no equivalent of the First Amendment to protect free speech. Many on both the left and the right would like to restrict the range of opinions capable of being expressed, at least through media they do not control (such as parts of the internet, as opposed to broadcast media over which the state has a monopoly or a press with whose owners successive Prime Ministers have an unhealthy relationship). But I believe very fundamentally in the right to the widest type of free speech when there is not a direct threat or incitement to something which is already a criminal act. And this would include views or statements which some will interpret as sexist, racist, anti-semitic, etc., or even a belief that terrible things should happen to someone, so long as this is not a direct incitement.

I generally block anyone on Twitter who says that anyone deserves to be hanged, to be raped in prison, or otherwise to be beaten up or mutilated – as often wished upon in the case of child abusers – or those who express approval for vigilantes or gangs thereof (including, for example, the female vigilante gangs in India). To my mind, those who do or wish such things are become little better than the abusers themselves. But I still do not believe at all that they should be criminalised for what they say.

In June, together with a group of others, I was involved in a Twitter campaign to get various MPs to add their names to those calling for a public inquiry into organised child abuse. As I discussed in a post I published on the eve of Simon Danczuk’s appearance before the Home Affairs Select Committee (which moved the campaign into another gear), I did not feel the persistent hectoring approach taken by some (and encouraged in that respect by Exaro News) was necessarily very productive. However, the campaign as a whole did undoubtedly result in many more MPs adding their names than would have otherwise been the case, and this played a fundamental part in Home Secretary Theresa May’s agreeing to the inquiry. A few people, including Labour MP Eric Joyce, and for a while former Conservative MP Mark Reckless, complained that this amounted to ‘online bullying’ (a refrain also taken up by some journalistic opponents of an inquiry, and doubtless privately by many other politicians). I would be very worried that in the future such politicians could threaten Twitter activists with this law to dissuade them from running such a campaign. The same would apply to Edwina Currie and her condescending and arrogant approach to questions which are put to her concerning abuse, or to numerous other politicians. Examples of these might be Harriet Harman MP, who is naturally not going to be happy with numerous tweeters reminding her of her earlier activities which served to help the Paedophile Information Exchange and their ideologies, or Lord Mayor of London Fiona Woolf, proposed chair of the inquiry, who has recently deleted her Twitter account after a period which has seen many tweets asking her questions about the nature of her personal and professional connections to various people themselves likely to come under scrutiny as part of the inquiry.

Be very distrustful of any laws, or any expansion of sentences linked to a law, which receive support first and foremost from politicians or others in power looking to criminalise ordinary people who attack them (when not in a manner actually constituting obviously criminal attack, as with Galloway). With more and more revelations coming to light about politicians, abuse and the corruption of power, there will be many angry people, some of whose statements to politicians on social media may unsurprisingly be intemperate. Do not let those politicians get away with criminalising their critics. So long as there are no direct threats involved, members of the public in a democracy should be free to be as harsh and offensive to politicians as they choose.

But I would ask whether the following hypothetical tweets would lead to two-year jail sentences against those who sent them?

@JimmySavile You are a vile abuser of children and necrophiliac protected at high levels of government

@PeterRighton Your proposed childcare reforms will make it easier for you to rape boys in homes

@PatriciaHewitt You submitted document to government saying child abuse does no harm, paedo defender

@PeterMorrison Did you miss the division bell because you were too busy seeking out adolescents in public toilets?

@CyrilSmith You are a hideous, obese and arrogant ass whose jokey exterior masks boy-raping scum

Peter Morrison and the cover-up in the Tory Party – fully updated

Posted: October 6, 2014 Filed under: Abuse, Conservative Party, Politics, Westminster | Tags: bryn alyn, bryn estyn, child abuse, chris house, christine russell, christopher grayling, conservatives, cyril smith, edwina currie, grahame nicholls, gyles brandreth, harriet harman, jack dromey, jillings report, jonathan aitken, labour, michael heseltine, nccl, nick davies, norman tebbit, operation pallial, paedophile information exchange, patricia hewitt, patrick cosgrove, peter morrison, pie, rob richards, stephen norris, teresa gorman, theresa may, william hague 14 Comments[This post has now been superseded by an updated version – please click onto that to see the most recent information on Morrison as well]

In Edwina Currie’s diary entry for July 24th, 1990, she wrote the following:

One appointment in the recent reshuffle has attracted a lot of gossip and could be very dangerous: Peter Morrison has become the PM’s PPS. Now he’s what they call ‘a noted pederast’, with a liking for young boys; he admitted as much to Norman Tebbit when he became deputy chairman of the party, but added, ‘However, I’m very discreet’ – and he must be! She either knows and is taking a chance, or doesn’t; either way it is a really dumb move. Teresa Gorman told me this evening (in a taxi coming back from a drinks party at the BBC) that she inherited Morrison’s (woman) agent, who claimed to have been offered money to keep quiet about his activities. It scares me, as all the press know, and as we get closer to the election someone is going to make trouble, very close to her indeed. (Edwina Currie, Diaries 1987-1992 (London: Little, Brown, 2002), p. 195)

The agent in question was Frances Mowatt. A 192 search reveals that there is now a Frances Mowatt, aged 65+, living in Billericay in Essex, Teresa Gorman’s old constituency.

The following are the recollections of Grahame Nicholls, who ran the Chester Trades Council (Morrison was the MP for Chester from 1974 to 1992), who wrote:

After the 1987 general election, around 1990, I attended a meeting of Chester Labour party where we were informed by the agent, Christine Russell, that Peter Morrison would not be standing in 1992. He had been caught in the toilets at Crewe station with a 15-year-old boy. A deal was struck between Labour, the local Tories, the local press and the police that if he stood down at the next election the matter would go no further. Chester finished up with Gyles Brandreth and Morrison walked away scot-free. I thought you might be interested. (cited in ‘Simon Hoggart’s week’, The Guardian, November 16th, 2012)

Sir Peter Morrison (1944-1995) was known, according to an obituary by Patrick Cosgrove, as a right winger who disliked immigration, supported the return of capital punishment, and wished to introduce vouchers for education. He was from a privileged political family; his father, born John Morrison, became Lord Margadale, the squire of Fonthill, led the campaign to ensure Alec Douglas-Home became Prime Minister in 1963, and predicted Thatcher’s ultimate accession to the leadership (Sue Reid, ‘Did Maggie know her closest aide was preying on under-age boys?’, Daily Mail, July 12th, 2014, updated July 16th). The young Peter attended Eton College, then Keble College, Oxford. Entering the House of Commons in 1974 at the age of 29, during the first Thatcher government he occupied a series of non-cabinet ministerial positions, then became Deputy Chairman of the Conservative Party in 1986, replacing Jeffrey Archer after his resignation, and working under Chairman Norman Tebbitt. His sister, Dame Mary Morrison, became a lady-in-waiting to the Queen (Gyles Brandreth, ”I was abused by my choir master’: In a brave and haunting account, TV star and ex MP Gyles Brandreth reveals the years of abuse he endured at prep school’, Daily Mail, September 12th, 2014).

Morrison was close to Thatcher from when he entered Parliament (see Thatcher, The Downing Street Years (London: Harper Collins, 1993), p. 837), working for her 1975 leadership campaign and, after she became Prime Minister, putting her and Denis up for holiday in the 73 000 acre estate owned by his father in Islay, where games of charades were played (Jonathan Aitken, Margaret Thatcher: Power and Personality (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), pp. 158-160, 279-281). After being appointed as Thatcher’s Parliamentary Private Secretary in 1990, he ran what is generally believed to have been a complacent and lacklustre leadership campaign for her when she was challenged by Michael Heseltine; as is well-known, she did not gain enough votes to prevent a second ballot, and then resigned soon afterwards. Morrison was known to some others as ‘a toff’s toff’, who ‘made it very clear from the outset that he did not intend spending time talking to the plebs’ on the backbenches (Stephen Norris, Changing Trains: An Autobiography (London: Hutchinson, 1996), p. 149).

Jonathan Aitken, a close friend of Morrison’s, would later write the following about him:

I knew Peter Morrison as well as anyone in the House. We had been school friends. He was the best man at my wedding in St Margaret’s, Westminster. We shared many private and political confidences. So I knew the immense pressures he was facing at the time when he was suddenly overwhelmed with the greatest new burden imaginable – running the Prime Minister’s election campaign.

Sixteen years in the House of Commons had treated Peter badly. His health had deteriorated. He had an alcohol problem that made him ill, overweight and prone to take long afternoon naps. In the autumn of 1990 he became embroiled in a police investigation into aspects of his personal life. The allegations against him were never substantiated, and the inquiry was subsequently dropped. But at the time of the leadership election, Peter was worried, distracted and unable to concentrate. (Aitken, Margaret Thatcher, pp. 625-626).

An important article by Nick Davies published in The Guardian in April 1998, also made the following claim:

Fleet Street routinely nurtures a crop of untold stories about powerful abusers who have evaded justice. One such is Peter Morrison, formerly the MP for Chester and the deputy chairman of the Conservative Party. Ten years ago, Chris House, the veteran crime reporter for the Sunday Mirror, twice received tip-offs from police officers who said that Morrison had been caught cottaging in public toilets with underaged boys and had been released with a caution. A less powerful man, the officers complained, would have been charged with gross indecency or an offence against children.

At the time, Chris House confronted Morrison, who used libel laws to block publication of the story. Now, Morrison is dead and cannot sue. Police last week confirmed that he had been picked up twice and never brought to trial. They added that there appeared to be no trace of either incident in any of the official records. (Nick Davies, ‘The sheer scale of child sexual abuse in Britain’, The Guardian, April 1998).

Recently, the former editor of the Sunday Mirror, Paul Connew, has revealed how he was told in 1994 by House of the stories concerning Morrison. Connew has revealed that it was a police officer who was the source, dismayed by the lack of action after Morrison had been arrested for sexually molesting under-age boys; the officer revealed how Morrison had attempted to ‘pull rank’ by demanding to see the most senior officer, and announcing proudly who he was. All the paperwork relating to the arrest simply ‘disappeared’. Connew sent a reporter to confront Morrison at his Chester home, but Morrison dismissed the story and made legal threats, which the paper was not able to counter without naming their police source, which was impossible. The story ultimately died, though Connew was able to establish that in the senior echelons of Scotland Yard, Morrison’s arrest and proclivities were no secret; he had been arrested on multiple occasions in both Chester and London, always hushed up (Paul Connew, ‘Commentary: how paedophile Peter Morrison escaped exposure’, Exaro News, September 26th, 2014).

In an article in the Daily Mail published in October 2012, former Conservative MP and leader of the Welsh Tories Rod Richards claimed that Morrison (and another Tory grandee who has not been named) was connected to the terrible abuse scandals in Bryn Estyn and Bryn Alyn children’s homes, in North Wales, having seen documents which identified both politicians as frequent, unexplained visitors. Richards also claimed that William Hague, who was Secretary of State for Wales from 1995 to 1997, and who set up the North Wales Child Abuse inquiry, would have seen the files on Morrison, but sources close to Hague denied that he had seen any such material. A former resident of the Bryn Estyn care home testified to Channel 4 News, testified to seeing Morrison arrive there on five occasions, and may have driven off with a boy in his car (‘Exclusive: Eyewitness ‘saw Thatcher aide take boys to abuse”, Channel 4 News, November 6th, 2012; see also Reid, ‘Did Maggie know her closest aide was preying on under-age boys?’).

Morrison’s successor as MP for Chester, Gyles Brandreth, wrote that he and his wife Michelle had been told on the doorstep repeatedly and emphatically that the MP was ‘a disgusting pervert’ (David Holmes, ‘Former Chester MP Peter Morrison implicated in child abuse inquiry’, Chester Chronicle, November 8th, 2012). More recently, in a build-up to the launch of a new version of Brandreth’s diaries, which suggested major new revelations but delivered little, Brandreth merely added that when canvassing in 1991 ‘we were told that Morrison was a monster who interfered with children’, and added:

At the time, I don’t think I believed it. People do say terrible things without justification. Beyond the fact that his drinking made Morrison appear unprepossessing — central casting’s idea of what a toff paedophile might look like — no one was offering anything to substantiate their slurs.

At the time, I never heard anything untoward about Morrison from the police or from the local journalists — and I gossiped a good deal with them. Four years after stepping down, Peter Morrison was dead of a heart attack.

What did Mrs Thatcher know of his alleged dark side? When I talked to her about him, I felt she had the measure of the man. She knew he was homosexual, and she knew he was a drinker. She was fond of him, clearly, but told me that he had ruined himself through ‘self-indulgence’ — much as Reginald Maudling had done a generation earlier. (Brandreth, ”I was abused by my choir master’)

Brandreth did however crucially mention that William Hague had told him in 1996 that Morrison’s name might feature in connection with the inquiry into child abuse in North Wales, specifically in connection to Bryn Estyn, thus corroborating Rod Richard’s account, though Brandreth also pointed out that the Waterhouse report made no mention of Morrison (Brandreth, ”I was abused by my choir master’).

The journalist Simon Heffer has also said that rumours about Morrison were circulating in Tory top ranks as early as 1988, whilst Tebbit has admitted hearing rumours ‘through unusual channels’, then confronting Morrison about them, which he denied (Reid, ‘Did Maggie know her closest aide was preying on under-age boys?’); Tebbit, who has suggested that a cover-up of high-level abuse by politicians is likely, now concedes that he had been ‘naive’ in believing Morrison, and rejected Currie’s account of Morrison having admitted his offences to him (James Lyons, ‘Norman Tebbit admits he heard rumours top Tory was paedophile a decade before truth revealed’, Daily Mirror, July 8th, 2014). The novelist Frederick Forsyth, on the other hand, described Morrison as someone ‘who should have been exposed many years ago’, as well as being a politically incompetent alcoholic; however, as far as his sexual offences were concerned, Forsyth claimed Thatcher ‘suspected nothing’ (Frederick Forsyth, ‘Debauched and dissolute fool’, The Express, July 18th, 2014)

Recently, Thatcher’s bodyguard Barry Strevens has come forward to claim that he told Thatcher directly about allegations of Morrison holding sex parties at his house with underage boys (one aged 15), when told about this by a senior Cheshire Police Officer. (see Lynn Davidson, ‘Exclusive: Thatcher’s Bodyguard on Abuse Claims’, The Sun on Sunday, July 27th, 2014 (article reproduced in comments below); and Matt Chorley, ‘Barry Strevens says he told Iron Lady about rumours about Peter Morrison’, Mail on Sunday, July 27th, 2014; see also Loulla-Mae Eleftheriou-Smith, ‘Thatcher ‘was warned of Tory child sex party claims’’, The Independent, July 27th, 2014). Strevens claimed to have had a meeting with the PM and her PPS Archie Hamilton (now Baron Hamilton of Epsom), which he had requested immediately. Strevens had claimed this was right after the Jeffrey Archer scandal; Archer resigned in October 1986, whilst Hamilton was Thatcher’s PPS from 1987 to 1988. Strevens recalls Thatcher simply thanking him and that was the last he heard of it. He said:

I wouldn’t say she (Lady Thatcher) was naive but I would say she would not have thought people around her would be like that.

I am sure he would have given her assurances about the rumours as otherwise she wouldn’t have given him the job.

The accounts by Nicholls and Strevens make clear that the allegations – concerning in one case a 15-year old boy – are more serious than said in a later rendition by Currie, which said merely that Morrison ‘had sex with 16-year-old boys when the age of consent was 21’ (cited in Andrew Sparrow, ‘Politics Live’, The Guardian, October 24th, 2012). A further allegation was made by Peter McKelvie, who led the investigation in 1992 into Peter Righton in an open letter to Peter Mandelson. A British Aerospace Trade Union Convenor had said one member had alleged that Morrison raped him, and he took this to the union’s National HQ, who put it to the Labour front bench. A Labour minister reported back to say that the Tory Front Bench had been approached. This was confirmed, according to McKelvie, by second and third sources, and also alleged that the conversations first took place at a 1993-94 Xmas Party hosted by the Welsh Parliamentary Labour Party. Mandelson has not yet replied.

In the 1997 election, Christine Russell herself displaced Brandreth and she served as Labour MP until 2010, when she was unseated by Conservative MP Stephen Mosely (see entry for ‘Christine Russell’ at politics.co.uk).

In 2013, following the publication of Hoggart’s article citing Nicholls, an online petition was put together calling for an inquiry, and submittted to then Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State Christopher Grayling. Russell denounced the ‘shoddy journalism’ of the Guardian piece, recalled rumours of Morrison’s preferences, but said there was no hint of illegal acts; she did not however rule out an agreement that Morrison should stand down (‘Campaigners ask for inquiry over ex-Chester MP’, Chester Chronicle, January 3rd, 2013).

Further questions now need to be asked of Lord Tebbit, Teresa Gorman, Edwina Currie, William Hague and other senior Tories, not to mention Christine Russell and others in Chester Labour Party, of what was known and apparently covered-up about Morrison. The identity of Morrison and Gorman’s agent (I could find no mention of a name in Gorman’s autobiography No, Prime Minister! (London: John Blake, 2001)) must be established [Edit: this has now been established as Frances Mowatt – see above] and she should be questioned if still around [Which she is, and living in Billericay, according to 192 directory – see above]. If money was involved, as Currie alleges was told to her by Gorman, then the seriousness of the allegations is grave. Just yesterday (October 5th), Currie arrogantly and haughtily declared on Twitter:

@MaraudingWinger @DrTeckKhong @MailOnline I’ve been nicer than many deserve! But I take the consequences, & I do not hide behind anonymity.

@jackaranian @Sunnyclaribel @woodmouse1 I heard only tiny bits of gossip. The guy is dead, go pursue living perps. You’ll do more good

@woodmouse1 @jackaranian @Sunnyclaribel The present has its own demands. We learn from the past, we don’t get obsessive about it. Get real.

@ian_pace @woodmouse1 @jackaranian @Sunnyclaribel And there are abusers in action right now, while you chase famous dead men.

@ian_pace @woodmouse1 @jackaranian @Sunnyclaribel I’d rather police time be spent now on today’s criminals – detect, stop and jail them

@jackaranian @Sunnyclaribel @woodmouse1 Flattered that you think I know so much. Sorry but that’s not so. If you do, go to police

@ian_pace @woodmouse1 @jackaranian @Sunnyclaribel They want current crimes to be dealt with by police, too. And they may need other help.

@ian_pace @woodmouse1 @jackaranian @Sunnyclaribel Of course. But right now, youngsters are being hurt and abused. That matters.

Considering Currie also rubber-stamped the appointment of Jimmy Savile at Broadmoor (Rowena Mason, ‘Edwina Currie voices regrets over Jimmy Savile after inquiry criticism’, The Guardian, Thursday June 26th, 2014) and clearly knew information about Morrison, including claims of bribery of a political agent, known to at least one other MP (Gorman) as well as herself, it should not be surprising that she would want claims of abuse involving dead figures to be sidelined.

This story relates to political corruption at the highest level, with a senior politician near the top of his party involved in the abuse of children, and clear evidence that various others knew about this, but did nothing, and strong suggestions that politicians and police officers conspired to keep this covered up, even using hush money, in such a way which ensured that Morrison was free to keep abusing others until his death. This story must not be allowed to die this time round.

Research Paper at City University, November 12th, on ”Clifford Hindley: The Scholar as Pederast and the Aestheticisation of Child Sexual Abuse”

Posted: October 3, 2014 Filed under: Abuse, Music - General, Musicology, PIE | Tags: Benjamin Britten, city university, Clifford Hindley, Home Office, j.z. eglinton, Kenneth Dover, laudan nooshin, mark sedwill, nambla, north american man-boy love association, paedophile information exchange, peter pears, peter righton, pie, tim hulbert 5 CommentsI will be giving a research paper at City University, London (where I am a Lecturer in Music) on November 12th, 2014, in Room AG09, College Building (on St John Street), at 6:30 pm (preceded by another staff presentation by Laudan Nooshin, entitled ‘Sites of Memory: Public Emotionality, Gender and Nationhood in the Music of Googoosh’ at 5:30 pm). This relates to my research into the late priest, Home Office civil servant and musicologist/classical scholar Clifford Hindley, and is as follows.

‘Clifford Hindley: The Scholar as Pederast and the Aestheticisation of Child Sexual Abuse’

The mysterious figure of J. Clifford Hindley, who died in 2006, is well-known to scholars of the music of Benjamin Britten for of a series of scholarly articles he published on Britten’s operas in the 1980s and 1990s. During the same period Hindley also published a few articles on Classical Greece, focusing upon Xenophon and Sappho. Less well-known is the fact that in the earlier part of his life, Hindley was an ordained priest who worked for a period in India and published a range of theological articles, then worked for a while at the Home Office in London, where he was head of the Voluntary Services Unit. This year, as part of wider investigations into organised sexual abuse, Hindley has been identified by former Home Office civil servant Tim Hulbert, who was Hindley’s junior at the department, as the individual responsible for ensuring that a total of £70 000 from Home Office funds was given to the Paedophile Information Exchange (PIE) in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

In this paper, for which I draw upon experience and expertise both as a critical/historical musicologist and as a campaigner and researcher on the subject of organised child abuse (especially in the field of classical music), I consider the obsessive focus upon paedophile themes in Hindley’s writings themselves, and locate his jargon, aestheticisation and ideologies within a wider tradition of contemporary paedophile writing since the 1960s, for which the volume Greek Love (New York: Oliver Layton Press, 1964) by J.Z. Eglinton (Walter Breen), a member of the North American Man-Boy Love Association (NAMBLA) who already had convictions for child abuse prior to the publication of this work, is a central text, leading to Kenneth Dover’s Greek Homosexuality (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978) – cited extensively by Hindley – which introduced the terms erastês and erômenos into the study of sexual exploitation of children, lending such activities a veneer of respectability through allusion to antiquity. I go on to consider this school of thought more widely in the context of a paedophile ‘sub-culture’ which achieved some prominence in the 1970s and 1980s.

This paper draws upon and extends and expands some earlier work published on my blog Desiring Progress (https://ianpace.wordpress.com ); some of this specific research has been used by various national news programmes in the UK, whilst the work on Hindley was requested in order to brief members of the Home Affairs Select Committee in July 2014 in advance of their questioning of the Home Office Permanent Secretary Mark Sedwill on issues of historical PIE infiltration of his department.

Antony Grey and the Sexual Law Reform Society 2

Posted: September 29, 2014 Filed under: Abuse, Labour Party, PIE, Westminster | Tags: albany trust, angela willans, antony grey, ben whitaker, Catherine Jay, christopehr bradbury-robinson, greek love, Helen Jay, j.z. eglinton, jo richardson, Judy Todd, keith hose, mary whitehouse, maurice yaffe, michael ingram, nambla, neville armstrong, paedophile action for liberation, paedophile information exchange, release, roger moody, theresa may, tony smythe, walter breen, william burroughs 6 CommentsA few articles were published by Dominic Kennedy in The Times in August of this year, relating to Antony Grey. I reproduce them here. One of them deals in particular with Grey’s role in the publication in the UK of J.Z. Eglinton’s book Greek Love (New York: Oliver Layton Press, 1964). Eglinton, whose real name was Walter Breen, was associated with NAMBLA, and was convicted for child molestation as early as 1954, then on various later occasions (involving boys aged 10 and above). This book is an absolutely key text in the paedophile canon.

The Times, July 23rd, 2014

Dominic Kennedy, ‘How paedophiles gained access to establishment by work with the young; Child sex campaigners boasted the education system could not cope without them’

Paedophiles became so entrenched in jobs working with children in the 1970s that one of their leaders suggested that if they staged a national strike many schools would close.

Campaigners openly admitted that men who were sexually attracted to children were being employed as teachers, clergymen, scoutmasters and youth workers.

The campaign to legalise sex at all ages gained access to the establishment via apparently progressive organisations such as mental health groups and gay and civil rights campaigns.

The evidence has emerged as the government prepares a national inquiry into historical child abuse.

The Times has discovered that childsex campaigners and doctors admitted that many paedophiles had found jobs working with children. Paedophile groups also wooed government-funded charities so that they could gain access to opinion formers. They also invented a “children’s rights” movement, campaigning on issues such as corporal punishment, as a cover for their real purpose of decriminalising sex between adults and children.

Roger Moody, writing for a magazine published by the campaign group Paedophile Awareness and Liberation (PAL), stated: “If all paedophiles in community schools or private schools were to strike, how many would be forced to close, or at least alter their regimes?”

In a factsheet prepared by the Paedophile Information Exchange (PIE), the organisation observed that teachers, clergymen, scoutmasters and youth workers were particularly prone to “child love”. It said: “Paedophiles are naturally drawn to work involving children, for which many of them have extraordinary talent and devotion (often they are also the ones the children value most). If this field were to be ‘purged’, there would be a damaging reduction of people left to do the work.”

Maurice Yaffe, a senior clinical psychologist, identified the same four professions in an article for a medical pamphlet, saying “it is fair to say that a high proportion will have sought out positions” in these fields.

The government-funded Albany Trust, a counselling service, was used by paedophile campaigners to gain access to influential people in society. “Recent talks with the Albany Trust have proved useful in a number of ways,” said an article in PAL’s newsletter, seen by The Times. “Firstly, the trust’s present policies are such that their co-operation has more to offer PAL than groups interested only in homosexuality. Secondly, the trust is in a position to provide useful contacts with other groups and organisations. [We will continue] to work with the Albany Trust in the coming months, and we are confident that this will not only be of great value to PAL and its members, but also as regards furthering the understanding and acceptance of paedophilia amongst non-paedophiles.”

This lobbying strategy bore fruit when Antony Grey, the director of the Albany Trust, privately urged Ben Whitaker, the former Labour MP for Hampstead, author and fellow executive member of the National Council for Civil Liberties, to discuss child sex at a forthcoming meeting with the chairman of WH Smith.

“I feel very strongly that Smiths should be called on to justify their attitude and not merely to use the word ‘paedophilia’ as a dirty brush with which to smear … anyone,” Mr Grey told Mr Whitaker. There is no reply in the archive. Albany Trust now says that it disassociates itself from organisations promoting child sex abuse.

PAL warned its subscribers “to use the utmost discretion in any communication with us” because police might seize their mail.

PIE was introduced to Albany Trust by the mental health charity Mind. The director of Mind at the time was also a senior figure in the NCCL, which accepted PIE and PAL as members. Mind has apologised.

PIE was helped by Release, the drug users’ charity. A submission from PIE to the Home Office, arguing for the decriminalisation of sex with children, gave Release’s offices as PIE’s holding address. Release said that it was “shocked and deeply upset that there was, or could have been, any connection between our work and the repugnant activities and despicable views promoted by PIE”.

An edition of PIE’s newsletter includes an art review by Christopher Bradbury-Robinson, a former head of English at a Home Counties preparatory school, describing “the eroticism of paedophilia … the yearning to touch the untouched”. Bradbury-Robinson became an author and friend of the novelist William Burroughs. Often mentioned in articles promoting paedophilia was Michael Ingram, a Catholic monk who portrayed himself as an expert in counselling and child sex, but was convicted in 2000 of sex offences against six boys during that era. He died after crashing his car into a wall.

The Labour MP Jo Richardson sent a supportive message to a PIE journal Childhood Rights saying that she supported its campaign against corporal punishment.

PIE infiltrated the Campaign for Homosexual Equality and PIE’s leader tabled a successful motion at its 1975 conference. He said that it was “absurd” for it to disassociate itself from paedophilia because there were “many gay paedophiles” inside and outside of the campaign group.

dkennedy@thetimes.co.uk

Who’s who from the era of misguided civil rights

Tony Smythe

(above) The national director of Mind, the mental health charity and a former general secretary of the National Council for Civil Liberties.

Antony Grey

director of the Albany Trust, secretary of Homosexual Law Reform Society, a member of the executives of the NCCL, Defence of Literature and the Arts Society and British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy.

Ben Whitaker

The first Labour MP for Hampstead (1966-1970). Executive director of Minority Rights Group. Head of George Orwell Memorial Trust. NCCL executive. Author. He was lobbied by Antony Grey to urge WH Smith, the newsagent, to stop using ‘ “paedophilia’ as a dirty brush with which to smear” anyone.

Christopher “CJ” Bradbury-Robinson

PIE magazine arts reviewer. Former prep school teacher. His friend William Burroughs referred to Bradbury-Robinson’s “sexual interest in small boys” in his introduction to a novel.

Michael Ingram

(below) Catholic monk who sent message of support to PIE’s magazine Childhood Rights. His purported research into child sexuality was taken seriously by experts in the 1970s but he was later exposed as a serial abuser of boys, jailed and died after crashing his car.

Jo Richardson

Feminist Labour MP. She thanked Childhood Rights for sending her a copy: “Of course I’ll support the campaign against corporal punishment,” she wrote.

GRAPHIC: Outraged women greet members of the Paedophile Information Exchange arriving for their first open meeting in London in 1977 with a barrage of eggs

NEVILLE MARRINER / REX FEATURES

Mary Whitehouse, the morality campaigner, delivers a 1.5 million signature petition against child sexual abuse to Downing St in 1978. Ben Whitaker, the Labour MP, campaigning in Hampstead with Catherine Jay, Judy Todd and Helen Jay, was an associate of Antony Grey

The Times, July 22nd, 2014

Dominic Kennedy, ‘Trust head helped edit book about sex with boys’

The head of a charity that received a government education grant secretly helped to edit a book about sex between boys and men, The Times can disclose.

Antony Grey, who was director of the Albany Trust, which provides counselling for homosexuals, protested his innocence when the morality campaigner Mary Whitehouse accused him of using taxpayers’ money to promote paedophilia. He omitted to disclose that he had already helped to produce the UK edition of Greek Love, a book by the American paedophile Walter Breen, who would eventually die in prison.

The book was on a recommended reading list issued by the Paedophile Information Exchange (PIE).

The Department for Education said yesterday that it would look into what payments were made to the trust, after The Times told it that the organisation reported receiving thousands of pounds a year in funding. It stated that in the late 1970s it was receiving money from the Home Office and what was then the Department of Education and Science.

Theresa May, the home secretary, published an independent investigation this month after it was realised that the Home Office had given grants to the trust. The review was unable to allay fears that some of the government funding may have been spent supporting the PIE campaign to legalise sex between children and adults.

A spokeswoman for the Department for Education said: “We will look in to the question of whether the department funded Albany Trust in the 1970s.”

The trust first came under the spotlight when Mrs Whitehouse claimed in a speech that it had been using grants to support paedophile groups. Mr Grey denied that any public money had been given to paedophiles.

He said in an article that he had attended a workshop by the charity Mind where a paedophile spoke “openly and bravely about his life situation”. He omitted to mention that the speaker was Keith Hose, the chairman of PIE.

PIE was affiliated to the influential National Council for Civil Liberties, whose executive included Mr Grey and Tony Smythe, the director of Mind.

Records seen by The Times show that the publisher Neville Armstrong wrote to Mr Grey in 1969 about Greek Love, a treatise about men having sex with boys written by Breen, a convicted paedophile, under the pseudonym J Z Eglinton. Breen died in 1993 while serving a ten-year sentence for child molesting. Mr Armstrong said he accepted Mr Grey’s editing suggestions. Mr Grey told the publisher: “Greek Love has caused me to rethink some of my own basic attitudes to human sexuality.”

The trust also proposed to publish a pamphlet about paedophiles which stated that they “represent no special threat to society”. It was abandoned after Angela Willans, a trustee who was the Woman’s Own agony aunt, saw a draft and branded it monstrous.

The Albany Trust said: “Albany Trust wishes to make it clear it entirely dissociates itself from any organisation promoting the sexual abuse of children. Albany’s counselling services continue to provide much-needed support for individuals from all backgrounds, across the spectrum of sexuality.”

It said that the trust adhered to a professional code of ethics.

Academia and Paedophilia 1: The Case of Jeffrey Weeks and Indifference to Boy-Rape

Posted: September 29, 2014 Filed under: Abuse, Academia, Labour Party, PIE, Westminster | Tags: andrew gilligan, bryan gould, Clifford Hindley, donald j. west, edward carpenter, eileen fairweather, esther saga, george thomas, germaine greer, harriet harman, jack dromey, jeffrey weeks, john parratt, kate millett, ken plummer, labour party, len davies, lord tonypandy, margaret hodge, mary mcintosh, mary mcleod, nccl, nettie pollard, paedophile information exchange, patricia hewitt, peter righton, pie, sheila rowbotham, tom o'carroll, warren middleton, yvette cooper 8 CommentsOver on the Spotlight blog, a series of important articles have been posted on paedophilia in academia, focusing on the work of sociologist Ken Plummer at the University of Essex, Len Davis, formerly Lecturer in Social Work at Brunel University, and Donald J. West, Professor of Clinical Criminology at the University of Cambridge. There is much more to be written on the issue of the acceptance of and sometimes propaganda for paedophilia in academic contexts; I have earlier published on the pederastic scholarly writings of Clifford Hindley (formerly a senior civil servant at the Home Office alleged to have secured funding for the Paedophile Information Exchange), as well as the pro-paedophile views of leading feminist and Cambridge University Lecturer Germaine Greer. In several fields, including sociology, social work, classical studies, art history, music, literature and above all gender and sexuality studies, there is much to be read produced in a academic environment, and published by scholarly presses, which goes some way towards the legitimisation of paedophilia. In July, Andrew Gilligan published an article on this subject as continues to exist in some academic summer conferences (Andrew Gilligan, ‘Paedophilia is natural and normal for males’, Sunday Telegraph, July 6th, 2014), whilst Eileen Fairweather has written about how easily many in academia were taken in by the language and rhetoric of PIE, as they ‘adroitly hijacked the language of liberation’, presented themselves in opposition to ‘patriarchy’ and would brand critics homophobic (Eileen Fairweather, ‘We on the Left lacked the courage to be branded ‘homophobic’, so we just ignored it. I wish I hadn’t’, Telegraph, February 22nd, 2014). Back in 1998 Chris Brand, Lecturer in Psychology at the University of Edinburgh, was removed from his post after advocating that consensual paedophilia with an intelligent child was acceptable (see Alastair Dalton, ‘Brand loses job fight over views on child sex’ The Scotsman, March 25th, 1988, reproduced at the bottom of this), but such cases are rare.

I would never advocate censorship of this material or research of this type, but I believe it to be alarming how little critical attention this type of material appears to receive, perhaps still because it is taboo in certain circles to criticise anything which in particular attaches itself to the cause of gay rights (just as victims of female abusers, or researchers into the subject, find themselves under continual attack from some feminists who would prefer for such abuse to continue than for it to disturb their tidy ideologies – see my earlier post on child abuse and identity politics).

I have over a period of time been assembling information on what I would call a paedophile ‘canon’ of writings, many of them produced by academics, which use similar ideologies and rhetoric to attempt to normalise and legitimise paedophilia. Detail on this will have to wait until a later date; for now, I want to draw attention to some of the writings of Emeritus Professor of Sociology and University Director of Research at South Bank University Jeffrey Weeks, previously Executive Dean of Arts and Human Sciences and Dean of Humanities. Rarely has Weeks’ work been subject to critique of this type (one notable exception is Mary Macleod and Esther Saga, ‘A View from the Left: Child Sexual Abuse’, in Martin Loney, Robert Bocock, et al (eds), The State or the Market: Politics and Welfare in Contemporary Britain (London: Sage Books, 1991), pp. 103-110, though this is problematic in other respects).

Weeks was described in a hagiographic article from 2008 as ‘the most significant British intellectual working on sexuality to emerge from the radical sexual movements of the 1970s’ (Matthew Waites, ‘Jeffrey Weeks and the History of Sexuality’, History Workshop Journal, Vol. 69, No. 1 (2010), pp. 258-266), having been involved the early days of the Gay Liberation Front and their branch formed at the London School of Economics in 1970. He published first in Gay News, and was a founding member of the Gay Left collective; their ‘socialist journal’ included several pro-paedophile articles (all can be downloaded here – see in particular issues 7 and 8). Weeks’ first book, Socialism and the New Life: the Personal and Sexual Politics of Edward Carpenter and Havelock Ellis (London: Pluto Press, 1977) was co-authored with Sheila Rowbotham; Rowbotham wrote on Edward Carpenter, who was a key member of the ‘Uranian’ poets, who have been described as ‘the forerunners of PIE’; the volume completely ignored any of this.

In the preface to the paedophile volume The Betrayal of Youth: Radical Perspectives on Childhood Sexuality, Intergenerational Sex, and the Social Oppression of Children and Young People (London: CL Publications, 1986), editor Warren Middleton (aka John Parratt, former vice-chair of the Paedophile Information Exchange and editor of Understanding Paedophilia, who was later jailed for possession of indecent images), acknowledged Weeks gratefully alongside members of the PIE Executive Committee and others who had ‘read the typescripts, made useful suggestion, and, where necessary, grammatical corrections’.

Here I am reproducing passages from four of Weeks’ books, which should make his positions relatively clear. The first gives a highly sanitised view of the paedophile movements PAL and PIE, accepting completely at face value the idea that they were simply ‘a self-help focus for heterosexual as well as homosexual pedophiles, giving mutual support to one another, exchanging views and ideas and encouraging research’, whose ‘method was the classical liberal one of investigation and public debate’ (rather than a contact group for abusers and for sharing images of child abuse, as was well-known and documented by this stage), and more concerned about the tabloid reaction than about their victims. It is a lousy piece of scholarship as well, considering this is a revised edition from 1997 (the book was earlier published in 1977, 1980 and 1993); Weeks breaks one of the first principles of scholarship by shelving information which does not suit his a priori argument, thus saying nothing about the various members of PIE who had been convicted and imprisoned (or fled the country) for offences against children, including most of its leading members, claiming that the involvement of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality was due to its being ‘gratutiously dragged in’, ignoring the fact of their having made public statements of support at their 1974 conference (of which Weeks, at the centre of this movement, would have been well-aware). The second, on ‘intergenerational sex’ (an academic term used to make paedophilia sound more acceptable) is backed up by a range of references which is almost like a who’s who of paedophile advocates, many treated as if reliable scholarly sources rather than the child abuse propaganda they are. In common with many left-liberal writers on paedophilia, he does not endorse sex between adult men and young girls, but applies a very different set of standards when boys are concerned. The third passage is more subtle, appearing to distance Weeks from the view of J.Z. Eglinton and others, but again (drawing upon Brian Taylor’s contribution to the volume Perspectives on Paedophilia) ends up trying to make distinctions in such a way that some child abuse is made less serious. The fourth takes an angle familiar from Peter Righton and others; as abuse mostly takes place in the family, the risks from other types of paedophiles end up being little more than a moral panic.

Weeks’ minimisation of concern about sexual exploitation of boys, and concomitant greater sympathy with gay abusers than their victims, resonates with the view coming from the Labour Party at the moment, with the Shadow Home Secretary Yvette Cooper determined to make child abuse purely an issue affecting girls. Furthermore, the Labour Deputy Leader Harriet Harman, as is now well-known, was involved at the centre of the National Council for Civil Liberties when they were closely linked to PIE (whose membership were overwhelmingly adult males looking to have sexual relations with boys). Under General Secretary Patricia Hewitt, NCCL submitted a document in 1976 to the Criminal Law Revision Committee, arguing amongst other things that ‘Childhood sexual experiences, willingly engaged in, with an adult result in no identifiable damage. The Criminal Law Revision Committee should be prepared to accept the evidence form follow-up research on child ‘victims’ which show that there is little subsequent effect after a child has been ‘molested’’, echoing PIE’s own submission on the subject. Harman was not involved with NCCL until two years later, but there is nothing to suggest policy changed during her time or she had any wish to change it, whilst during her tenure NCCL went on to advertise in PIE’s house journal Magpie, and had Nettie Pollard, PIE member No. 70, as their Gay and Lesbian Officer. This was the heyday of PIE, and the support of NCCL was a significant factor. Harman, quite incredibly, went on to make paedophile advocate Hewitt godmother to her sons. Cooper is of a different generation, but all her pronouncements suggest the same contemptuous attitude towards young boys, seeing them only as threats to girls and near-animals requiring of taming, rarely thinking about their needs nor treating them as the equally sensitive and vulnerable people they are; with this in mind, abuse of boys is an issue she almost never mentions. It is alarming to me that both Harman and Cooper have parented sons and yet appear to be entirely unwilling to accept that boys deserve equal love and respect, nor keen to confront the scale of organised institutional abuse of boys

Though considering the number of stories involving Labour figures alleged to have abused or colluded with the abuse of young boys (I think of the cases in Leicester, Lambeth, the relationship of senior Labour figures to PIE, not just Harman, her husband Dromey, and Hewitt, but also former leadership candidate Bryan Gould, who made clear his endorsement for the organisation (see also this BBC feature from earlier this year; the relationship of the late Jo Richardson to the organisation also warrants further investigation), not to mention the vast amount of organised abuse which was able to proceed unabated in Islington children’s homes when the council was led by Margaret Hodge, who incredibly was later appointed Children’s Minister, the allegations around former Speaker of the House of Commons George Thomas aka Lord Tonypandy, and some other members of the New Labour government who have been identified as linked to Operation Ore; and the support and protection afforded to Peter Righton by many on the liberal left), it is not surprising if the Labour frontbench want to make the sexual abuse of boys a secondary issue. This is unfortunately a common liberal-left view, and a reason to fear the consequences of some such people being in charge of children at all, whether as parents or in other roles. There are those who see young boys purely as a problem, little more than second-best girls, to be metaphorically beaten into shape, though always viewed as dangerous, substandard, and not to be trusted; this in itself is already a type of abuse, but such a view also makes it much easier to overlook the possibility their being sexually interfered with and anally raped (not to mention also being the victims of unprovoked violence) – the consequences are atrocious. Many young boys were sexually abused by members of the paedophile organisation that Harman, Hewitt, Dromey et al helped to legitimise (I am of a generation with many of the boys who appeared in sexualized pictures aged around 10 or under in the pages of Magpie; I was fortunate in avoiding some of their fate, others were not); it is right that they should never be allowed to forget this, and it thoroughly compromises their suitability for public office. The Labour Party and the liberal left in general, have a lot of work to do if they are not to be seen as primary advocates for and facilitators for boy rape. In no sense should this be seen as any type of attack on the fantastic work done by MPs such as Simon Danczuk, Tom Watson or John Mann, or many other non-politicians working in a similar manner; but the left needs rescuing from a middle-class liberal establishment who are so blinkered by ideology as to end up dehumanising and facilitating the sexual abuse of large numbers of people. Weeks, Plummer, West, Davies, Greer, Millett, Hindley, and others I will discuss on a later occasion such as Mary McIntosh, are all part of this tendency.

Jeffrey Weeks, Coming Out: Homosexual Politics in Britain from the Nineteenth Century to the Present, revised and updated edition (London & New York: Quartet Books, 1997)

‘Even more controversial and divisive was the question of pedophilia. Although the most emotive of issues, it was one which centrally and radically raised the issue of the meaning and implications of sexuality. But it also had the disadvantage for the gay movement that it threatened to confirm the persistent stereotype of the male homosexual as a ‘child molester’. As a result, the movement generally sought carefully to distance itself from the issue. Recognition of the centrality of childhood and the needs of children had been present in post-1968 radicalism, and had found its way into early GLF ideology. The GLF gave its usual generous support to the Schools Action Union, a militant organization of schoolchildren, backed the short-lived magazine Children’s Rights in 1972, campaigned against the prosecutions of Oz (for the schoolchildren’s issue) and the Little Red Schoolbook. But the latter, generally a harmless and useful manual for children, illustrated the difficulties of how to define sexual contact between adults and children in a non-emotive or moralistic way. In its section on this, the Little Red Schoolbook stressed, rightly, that rape or violence were rare in such contacts, but fell into the stereotyped reaction by talking of ‘child molesting’ and ‘dirty old men’: ‘they’re just men who have nobody to sleep with’; and ‘if you see or meet a man like this, don’t panic, go and tell your teacher or your parents about it’. [28]

But the issue of childhood sexuality and of pedophile relationships posed massive problems both of sexual theory and of social practice. If an encounter between child and adult was consensual and mutually pleasurable, in what way could or should it be deemed harmful? This led on to questions of what constituted harm, what was consent, at what age could a child consent, at what age should a child be regarded as free from parental control, by what criteria should an adult sexually attracted to children be judged responsible? These were real questions which had to be faced if any rational approach was to emerge, but too often they were swept aside in a tide of revulsion.

A number of organizations in and around the gay movement made some effort to confront these after 1972 on various levels. Parents Enquiry, established in South London in 1972 by Rose Robertson, attempted to cope with some of the problems of young homosexuals, particularly in their relationships with their parents. Her suburban middle-class respectability gave her a special cachet, and with a series of helpers she was able to help many young people to adjust to their situation by giving advice, holding informal gatherings, mediating with parents and the authorities. [29] More radical and controversial were two pedophile self-help organizations which appeared towards the end of 1974: PAL (originally standing for Pedophile Action for Liberation) and PIE (Pedophile Information Exchange). Their initial stimulus was the hostility they felt to be directed at their sexual predilections within the gay movement itself, but they both intended to act as a self-help focus for heterosexual as well as homosexual pedophiles, giving mutual support to one another, exchanging views and ideas and encouraging research. The sort of gut reaction such moves could provoke was illustrated by a Sunday People ‘exposé’ of PAL, significantly in the Spring Bank Holiday issue in 1975. It was headed ‘An Inquiry that will Shock every Mum and Dad’, and then, in its boldest type, ‘The Vilest Men in Britain’. [30] Despite the extreme hyperbole and efforts of the paper and of Members of Parliament, no criminal charges were brought, since no illegal deeds were proved. But it produced a scare reaction in parts of the gay movement, especially as CHE had been gratuitously dragged in by the newspaper.

Neither of the pedophile groups could say ‘do it’ as the gay liberation movement had done, because of the legal situation. Their most hopeful path lay in public education and in encouraging debate about the sexual issues involved. PIE led the way in this regard, engaging in polemics in various gay and non-gay journals, conducting questionnaires among its membership (about two hundred strong) and submitting evidence to the Criminal Law Revision Committee, which was investigating sexual offences. [31] PIE’s evidence, which advocated formal abolition of the age of consent while retaining non-criminal provisions to safeguard the interests of the child against violence, set the tone for its contribution. Although openly a grouping of men and women sexually attracted to children (and thus always under the threat of police investigation), the delicacy of its position dictated that its method was the classical liberal one of investigation and public debate. Significantly, the axes of the social taboo had shifted from homosexuality to conceptually disparate forms of sexual variation. For most homosexuals this was a massive relief, and little enthusiasm was demonstrated for new crusades on wider issues of sexuality. (pp. 225-227)

28. Sven Hansen and Jasper Jensen, The Little Red School-book, Stage 1, 1971, p. 103. See the ‘Appeal to Youth’ in Come Together, 8, published for the GLF Youth Rally, 28 August 1971.

29. See her speech to the CHE Morecambe Conference, quoted in Gay News, 21.

30. Sunday People, 25 May 1975. For the inevitable consequences of this type of unprincipled witchhunt, see South London Press, 30 May 1975: ‘Bricks hurled at “sex-ring” centre house’, describing an attack on one of the addresses named in the Sunday People article.

31. There is a brief note on PIE’s questionnaire in New Society, vol. 38, No. 736, 11 November 1976, p. 292 (‘Taboo Tabled’).

Jeffrey Weeks, Sexuality and its Discontents: Meanings, Myths & Modern Sexualities (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985).

Intergenerational sex and consent

If public sex constitutes one area of moral anxiety, another, greater, one, exists around intergenerational sex. Since at least the eighteenth century children’s sexuality has been conventionally defined as a taboo area, as childhood began to be more sharply demarcated as an age of innocence and purity to be guarded at all costs from adult corruption. Masturbation in particular became a major topic of moral anxiety, offering the curious spectacle of youthful sex being both denied and described, incited and suppressed. ‘Corruption of youth’ is an ancient charge, but it has developed a new resonance over the past couple of centuries. The real curiosity is that while the actuality is of largely adult male exploitation of young girls, often in and around the home, male homosexuals have frequently been seen as the chief corrupters, to the extent that in some rhetoric ‘homosexual’ and ‘child molesters’ are coequal terms. As late as the 1960s progressive texts on homosexuality were still preoccupied with demonstrating that homosexuals were not, by and large, interested in young people, and even in contemporary moral panics about assaults on children it still seems to be homosexual men who are investigated first. As Daniel Tsang has argued, ‘the age taboo is much more a proscription against gay behaviour than against heterosexual behaviour.’ [30] Not surprisingly, given this typical association, homosexuality and intergenerational sex have been intimately linked in the current crisis over sexuality.

Alfred Kinsey was already noting the political pay-off in child-sex panics in the late 1940s. In Britain in the early 1960s Mrs Mary Whitehouse launched her campaigns to clean up TV, the prototype of later evangelical campaigns, on the grounds that children were at risk, and this achieved a strong resonance. Anita Bryant’s anti-gay campaign in Florida from 1976 was not accidentally called ‘Save Our Children, Inc.’. Since these pioneering efforts a series of moral panics have swept countries such as the USA, Canada, Britain and France, leading to police harassment of organisations, attacks on publications, arrests of prominent activists, show trials and imprisonments. [31] Each panic shows the typical profile, with the escalation through various stages of media and moral manipulation until the crisis is magically resolved by some symbolic action. The great ‘kiddie-porn’ panic in 1977 in the USA and Britain led to the enactment of legislation in some 35 American states and in Britain. The guardians of morality may have given up hope of changing adult behaviour, but they have made a sustained effort to protect our young, whether from promiscuous gays, lesbian parents or perverse pornographers. [32]