Be very sceptical about online communications laws which protect the powerful – social media and the right to offend

Posted: October 20, 2014 Filed under: Abuse, Conservative Party, History, Labour Party, Liberal Democrats, Politics, Westminster | Tags: alan dershowitz, angela merkel, cecil parkinson, censorship, chris grayling, david k. nelson, david mellor, edwina currie, eric joyce, fiona woolf, freedom of speech, george galloway, gerald scarfe, harold washington, harold wilson, harriet harman, home affairs select committee, israel, latuff, lindon baines johnson, malicious communications act, margaret thatcher, mark reckless, mark rowson, martin rowson, napoleon, paedophile information exchange, palestine, peter morrison, richard newton, robert walpole, sarah ferguson, simon danczuk, stella creasy, steve bell, tony blair 4 CommentsToday the UK Justice Secretary, Chris Grayling, clarified that what he called ‘a baying cyber-mob’ could face up to two years in jail under new laws. This refers to proposed amendments to the 1988 Malicious Communications Act, to quadruple the maximum sentence. Already, as modified in 2001 (modifications indicated), the law defines the following offence:

1. Offence of sending letters etc. with intent to cause distress or anxiety

Any person who sends to another person—

(a)a [F1 letter, electronic communication or article of any description] which conveys—

(i)a message which is indecent or grossly offensive;

(ii)a threat; or

(iii)information which is false and known or believed to be false by the sender; or

(b)any [F2 article or electronic communication] which is, in whole or part, of an indecent or grossly offensive nature,

is guilty of an offence if his purpose, or one of his purposes, in sending it is that it should, so far as falling within paragraph (a) or (b) above, cause distress or anxiety to the recipient or to any other person to whom he intends that it or its contents or nature should be communicated.

(2)A person is not guilty of an offence by virtue of subsection (1)(a)(ii) above if he shows—

(a)that the threat was used to reinforce a demand [F3 made by him on reasonable grounds]; and

(b)that he believed [F4, and had reasonable grounds for believing,] that the use of the threat was a proper means of reinforcing the demand.

[F5 (2A)In this section “electronic communication” includes—

(a)any oral or other communication by means of a telecommunication system (within the meaning of the Telecommunications Act 1984 (c. 12)); and

(b)any communication (however sent) that is in electronic form.]

(3)In this section references to sending include references to delivering [F6 or transmitting] and to causing to be sent [F7, delivered or transmitted] and “sender” shall be construed accordingly.

(4)A person guilty of an offence under this section shall be liable on summary conviction to [F8 imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months or to a fine not exceeding level 5 on the standard scale, or to both].

Under the new amendments, the maximum sentence would be two years.

Direct physical or other threats are indeed a worrying phenomenon of social media, as are any threats to politicians or others in public life, and I have no problem with these being criminalised. But it is clear that this law goes much further than that. In particular, the terms ‘indecent’ and ‘grossly offensive’ are very nebulous, and could be used in highly censorious ways, as I will attempt to demonstrate presently.

Amongst those cited in support of Grayling’s laws are former Conservative MP Edwina Currie and Labour MP Stella Creasy. A 33-year old man, Peter Nunn, received an 18-month sentence for abusive Twitter messages against Creasy. Yet Creasy’s rank hypocrisy was amply demonstrated when challenged by myself and various others some weeks ago to condemn a case where violence was not merely threatened but actually carried out, in a frenzied attack against Respect MP George Galloway by Neil Masterson, who appears to be a neo-fascist supporter of the Israeli government. The 60-year old Galloway was leaped on in a frenzied manner by the attacker, and suffered a broken jaw, suspected broken rib and severe bruising to the head and face through the attack. There were a shocking number of people posting online in many places to say Galloway deserved it.

Just a few prominent commentators made an issue of this. Peter Oborne, writing in the Telegraph, drew attention to the fact that no political party leader, nor the Speaker of the House of Commons, had condemned this attack on Galloway, which Oborne called ‘beyond doubt an attack on British democracy itself’. He added:

Had an MP been attacked by some pro-Palestinian fanatic for his support of Israel, I guess there would have been a national outcry and rightly so. Why then the silence from the mainstream establishment following this latest outrageous assault on a British politician?

Times journalist Hugo Rifkind, no political supporter of Galloway, tweeted on 31/8 ‘What happened to @georgegalloway shouldn’t happen to any politician in this country. Horrifying. Hope he’s okay.’

Amongst the responses were one by @77annfield, who said ‘any physical attack is wrong but it was his personality that brought it on’ (i.e. he basically deserved it), a few days later by an @ElectroPig who said ‘It shouldn’t happen to an HONEST politician who actually gives a damn. The rest of the bastards? #FineByMe’.

No UK party leader nor prominent politician condemned this attack on a fellow MP. Can we presume that Creasy thinks physical assault is OK, or at least not much of an issue, when it is against a political opponent or someone she doesn’t like? I am quite sure that if Creasy had suffered such an attack, and had her jaw and ribs broken, Galloway would have wholeheartedly condemned it.

Edwina Currie is currently the subject of various scrutiny for her role in appointing Jimmy Savile to a taskforce to run Broadmoor prison,, where he was involved in widespread sexual abuse, and also for the fact that she knew about the paedophile activities of late Conservative MP Peter Morrison, but appeared to do nothing about it until she could use it in diaries she had to sell. She said on the subject of Grayling’s proposals:

Most people know the difference between saying something nice and saying something nasty, saying something to support, which is wonderful when you get that on Twitter, and saying something to wound which is very cruel and very offensive.

it should not be surprising if Currie only wants ‘nice’ things said about her, considering her record. But the freedom to say things which are cruel, very offensive, and may be designed to wound, is fundamental in a democracy, I would say, however much Currie may not wish it to be. I worry about the implications of this law more widely to be possibilities of political dissent and satire in an age in which electronic communications and social media play a more prominent role than ever.

With this in mind, I would strongly recommend watching the two part 1994 BBC series written and presented by Kenneth Baker (now Lord Baker), From Walpole’s Bottom to Major’s Underpants, tracing the history of the political cartoon.

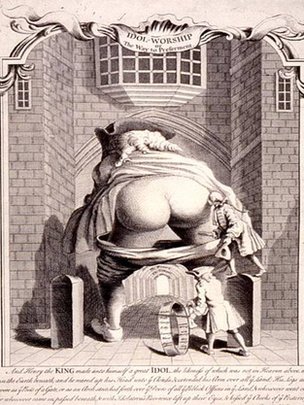

The image below, produced anonymously in 1740, refers to Robert Walpole, Prime Minister from 1721 to 1742.

This dates from 1797, and is by Richard Newton, showing Pope Pius VI kissing the bare bottom of Napoléon Bonaparte.

More recently, this image from 1967, drawn by Gerald Scarfe for Private Eye, shows Harold Wilson pulling down the back of Lindon Baines Johnson’s trousers and pants, as a comment on the Vietnam War; the original image actually had Wilson’s tongue up Johnson’s bottom, but then-editor Richard Ingrams thought this was too much.

This 1988 image, Mirth and Girth by then School or Art Institute of Chicago student David K. Nelson Jr, is of former Chicago major Harold Washington. This picture was confiscated by Chicago police, though Nelson later won a federal lawsuit against the city on the grounds of the confiscation and damage to his picture.

This from 2006, by cartoonist Latuff, shows fundamentalist pro-Israel zealot Alan Dershowitz masturbating over the sight of carnage in Lebanon brought about through Israeli military action.

This cartoon from Martin Rowson from 2007 at the time of Tony Blair’s resignation as Prime Minister, hardly hides its ‘fuck off and die’ message.

And here, from 2012, is a Steve Bell cartoon portraying Angela Merkel as a dominatrix of Europe.

Other example would include a bare-breasted Margaret Thatcher on Spitting Image (which I have been unable to find to post here), and countless other images from that programme (look at the treatment of Cecil Parkinson, David Mellor or Sarah Ferguson, for example, after all were embroiled in sex scandals).

All of these could be more than plausibly described as ‘indecent’ (except perhaps the Rowson cartoon) and ‘grossly offensive’. They all appeared in mainstream publications, but what would happen if a cartoonist posted them online, and tweeted them, perhaps with the hashtag of their subjects included? If they would be liable for prosecution and possibly a two-year prison sentence, this would be an extremely worrying development indeed.

I have seen and experienced intimidation online by other pro-Israeli neo-fascists, who spread messages of sometimes violent hatred. Some students have been revealed to have been paid by the Israeli government to act as propagandists, and I would imagine some of the people I have encountered are amongst these. I cannot imagine these laws being used against them (and certainly have not heard of such a case), though in the future I could certainly imagined them being used to intimidate pro-Palestinian campaigners, by branding various views they might express (such as, for example, that the foundation of the state of Israel involved the dispossession and ethnic cleansing of Palestinians, and cannot be accepted as legitimate) as ‘anti-semitic’, and as such constituting quasi-hate crimes against those to whom they are addressed. In neither of these cases is criminalisation appropriate.

In the UK, there is no written constitution as such, and thus no equivalent of the First Amendment to protect free speech. Many on both the left and the right would like to restrict the range of opinions capable of being expressed, at least through media they do not control (such as parts of the internet, as opposed to broadcast media over which the state has a monopoly or a press with whose owners successive Prime Ministers have an unhealthy relationship). But I believe very fundamentally in the right to the widest type of free speech when there is not a direct threat or incitement to something which is already a criminal act. And this would include views or statements which some will interpret as sexist, racist, anti-semitic, etc., or even a belief that terrible things should happen to someone, so long as this is not a direct incitement.

I generally block anyone on Twitter who says that anyone deserves to be hanged, to be raped in prison, or otherwise to be beaten up or mutilated – as often wished upon in the case of child abusers – or those who express approval for vigilantes or gangs thereof (including, for example, the female vigilante gangs in India). To my mind, those who do or wish such things are become little better than the abusers themselves. But I still do not believe at all that they should be criminalised for what they say.

In June, together with a group of others, I was involved in a Twitter campaign to get various MPs to add their names to those calling for a public inquiry into organised child abuse. As I discussed in a post I published on the eve of Simon Danczuk’s appearance before the Home Affairs Select Committee (which moved the campaign into another gear), I did not feel the persistent hectoring approach taken by some (and encouraged in that respect by Exaro News) was necessarily very productive. However, the campaign as a whole did undoubtedly result in many more MPs adding their names than would have otherwise been the case, and this played a fundamental part in Home Secretary Theresa May’s agreeing to the inquiry. A few people, including Labour MP Eric Joyce, and for a while former Conservative MP Mark Reckless, complained that this amounted to ‘online bullying’ (a refrain also taken up by some journalistic opponents of an inquiry, and doubtless privately by many other politicians). I would be very worried that in the future such politicians could threaten Twitter activists with this law to dissuade them from running such a campaign. The same would apply to Edwina Currie and her condescending and arrogant approach to questions which are put to her concerning abuse, or to numerous other politicians. Examples of these might be Harriet Harman MP, who is naturally not going to be happy with numerous tweeters reminding her of her earlier activities which served to help the Paedophile Information Exchange and their ideologies, or Lord Mayor of London Fiona Woolf, proposed chair of the inquiry, who has recently deleted her Twitter account after a period which has seen many tweets asking her questions about the nature of her personal and professional connections to various people themselves likely to come under scrutiny as part of the inquiry.

Be very distrustful of any laws, or any expansion of sentences linked to a law, which receive support first and foremost from politicians or others in power looking to criminalise ordinary people who attack them (when not in a manner actually constituting obviously criminal attack, as with Galloway). With more and more revelations coming to light about politicians, abuse and the corruption of power, there will be many angry people, some of whose statements to politicians on social media may unsurprisingly be intemperate. Do not let those politicians get away with criminalising their critics. So long as there are no direct threats involved, members of the public in a democracy should be free to be as harsh and offensive to politicians as they choose.

But I would ask whether the following hypothetical tweets would lead to two-year jail sentences against those who sent them?

@JimmySavile You are a vile abuser of children and necrophiliac protected at high levels of government

@PeterRighton Your proposed childcare reforms will make it easier for you to rape boys in homes

@PatriciaHewitt You submitted document to government saying child abuse does no harm, paedo defender

@PeterMorrison Did you miss the division bell because you were too busy seeking out adolescents in public toilets?

@CyrilSmith You are a hideous, obese and arrogant ass whose jokey exterior masks boy-raping scum

[…] Be very sceptical about online communications laws which protect the powerful – social media and t… (20/10/14) […]

Dear Mr Pace, I support your work regarding exposing child abuse and commend your work in this area. However having read your article and seeing some of your views on Israel I feel we are not in agreement as I am quite pro – Israel. For this reason I have decided to unsubscribe to your online email

Kind Regards

Penny Housley

>

[…] Be very sceptical about online communications laws which protect the powerful – social media and t… (20/10/14) […]

[…] I cannot believe this resemblance is merely coincidental. What have we come to when a leading British newspaper is describing Muslim migrants and refugees to Europe using imagery and associations lifted directly from Nazi anti-semitic propaganda? Addendum: Whilst I do not share the view of the cartoon presented here by Dave Brown, I would not advocate censorship, for reasons laid out in another blog post from last year. […]