New Music 1 – A Niche World

Posted: July 29, 2022 Filed under: Academia, Culture, Music - General, Musical Education, Musicology, New Music, Uncategorized | Tags: anne boissiere, arnold schoenberg, atonality, berlin novembergruppe, bjorn heile, charles wilson, cold war, Dick Hebdige, Donald Martino, gary e. mcpherson, makis solomos, Martin Iddon, milton babbitt, moderne, modernism, modernisme, modernismo, New Modernist Studies, New Music, nicholas cook, oxford handbook of music performance, paul bekker, richard taruskin, richard toop, robert walker, roger sessions, routledge research companion to modernism in music, subculture, susan mcclary, terminal prestige, the composer as specialist, theodor adorno, universities, who cares if you listen? 4 CommentsIn several recent writings and various upcoming ones I have been considering in a more sustained fashion wider aspects of the culture of new music, both historically and in the present day. My long chapter, just published, ‘New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices’, in The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance, Volume 1, edited Gary E. McPherson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), pp. 396-455, traces the growth of a network of festivals, concert series and other aspects of a new music infrastructure from after the end of World War One, as well as the development of specialised performance skills on the part of individual interpreters and ensembles, all as part of a specific culture of ‘new music’ which developed with a degree of autonomy from a more mainstream culture of art music performance (as represented by orchestral, chamber, choral, solo concerts of repertoire primarily from the common practice period) over the course of a century. This very fact of inhabiting a separate realm is to me a defining aspect of new music, a term which has developed ever since the publication of Paul Bekker’s vital essay ‘Neue Musik’ (1919), advocating a range of new approaches to music, some of them then still relatively latent, which constituted a significant break with or at least shift of emphasis from the immediate past, one which was amplified at a time which saw the collapse of various aspects of the pre-war order, revolution in Russia, and an attempt revolution in Germany, which members of the influential Berlin Novembergruppe sought to sublimate into artistic creation.

In ‘Modernist Fantasias: The Recuperation of a Concept’, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, vol. 144, no. 2 (2019), pp. 473-493, starting from a detailed critical examination of The Routledge Research Companion to Modernism in Music, edited Björn Heile and Charles Wilson (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2019), I consider the provenance and development of the term ‘modernism’ (and its equivalents such as French modernisme, German Moderne, Spanish modernismo and so on) both in music and other arts, not least in terms of recent attempts to frame the concept more broadly than hitherto (in some cases to date it back to the French Revolution) as well as to recapture it as a living force deserving of reconsideration, as informed the so-called New Modernist Studies in literary and cultural scholarship beginning in 1999, which has been matched more gradually by the growth of parallel scholarship in music. I have also been working on a book chapter considering the historiography of new music since 1989, and recently gave a lecture looking more broadly at historiographical issues through the 20th and 21st century, which have also been the theme of other lectures and publications considering the ways in which ‘experimental’ and ‘minimal’ music have informed such historiography.

All of this work, combined with my ongoing work on the creation and development of the infrastructure for new music in post-1945 Germany, have brought to the fore difficult questions relating to new music as a whole and its place today. I have been professionally active as a pianist in the world of new music for three decades, and have become intimately aware of its range of mores, orthodoxies, internal politics, and so on, and the ways in which its institutions and those operating those tend to work. It remains a field of cultural activity which in my opinion has immense value, but claims for its wider importance and significance are less easy to articulate in a manner which might convince those who need convincing. But this latter activity, if one believes this importance to be the case (which I do, but in a less unequivocal manner than I might have done 15-20 years ago), is vital if those engaged with new music seek an impact and respect beyond the narrow realms of fellow travellers. This is not so often to be found, and a reticence to engage with the wider issues concerned suggests either dangerous complacency or even a wilful disregard married to a sense of entitlement, which I believe should be challenged.

I am fully aware that there are a great many who would describe a lot of the atonal music I play (and even some of the more dissonant late tonal music as well), and which those I know compose, at the politest as ‘not music’, often through much harsher derogatory epithets. These will include some friends, some students and many other members of the wider public with no personal investment in this work nor necessarily any desire for such. It is much too easy to dismiss those who think in such a way as idiots, philistines, etc., in the process writing off large swathes of any population. But in my experience those who think such a way do not particular care unless they feel made to listen to such music, whether in a performance situation where it is not their reason for being there, feeling it is imposed upon them in education, or in the face of stentorian claims about its importance.

Yet one might struggle to be aware of this within the rarefied circles of those professionally involved in new music. That a great many people might be not simply indifferent but actively hostile to their music in the contexts described above can seem a subject which it is unacceptable even to consider. That the work of musicians involved must be vital and must deserve the widest support is an article of faith, or at least amongst different factions of individuals, who do not necessarily extend this view to members of rival factions. Some looking from outside might be shocked to see the extent of the personalised vitriol extended by some towards anyone (not least critics, but also various others) who aver an opinion that they do not find some piece of music engaging, moving, or some other quality they seek. The response can be to pathologise those who think such a way, or seek to disallow their opinions from being heard. Following the recent death of Richard Taruskin, there was a furious set of posts on social media about a highly critical review he wrote of two CDs of the American composer Donald Martino, which extended into a wider critique of aspects of new music (see below). The view seemed to be that the only type of legitimate review is one which praises this type of work, and anything else should not be allowed to be printed. It would be interesting to see this principle applied to restaurant reviewing – I am sure some restaurant owners would be more than happy.

There are ways to frame new music and its particularity which avoid the need to make wider claims for its public significance. In a 2014 article, Martin Iddon conceptualised new music as a type of ‘subculture’, drawing upon the concept propounded most notoriously by Dick Hebdige in his 1979 book Subculture: The Meaning of Style. I have used this concept myself in my ‘New Music’ article mentioned above, but have doubts (some reservations expressed in a footnote there did not make it into the final version!). Certainly new music has from the outset entailed a realm of activity distinct from a ‘mainstream’, as is true of many subcultures explored and theorised by Hebdige and others (space does not allow consideration here of the later concept of ‘post-subculture’). But its economic situation is not at all comparable with the subculture of the mods, rockers, punks or whatever. In large measure, new music activity relies heavily on subsidy for its continued operation; it would not be financially viable via ticket sales alone, other than very small operations. This subsidy comes either from public money generated through taxation and distributed in various ways via local, regional and state arts organisations, as is the case in much of Western Europe and to a lesser extent the UK (though considerably less so in the United States), or through the patronage of universities, in which those involved in new music production may find employment and some concomitant financial support for their activities. These things lend such music a level of institutional or official prestige which is quite uncharacteristic of other forms of subculture. If one could imagine a group of death metal fans receiving regular government grants to develop their music, clothing, writings, and so on, and present these in major government-backed venues, this would surely seem a long way from the conventional idea of a subculture.

Here subcultural theory does present one phenomenon which is familiar in part: numerous studies observe how subcultures, despite defining themselves in opposition to some mainstream, exhibit marked homologous tendencies and appear to require a degree of discipline and unity from their own members, with little tolerance for internal dissent. In the case of new music circles, it would be untrue to deny the existence of divisions, because of the opposing factions mentioned earlier. But these are divisions between different groups competing for the mantle of new music, seen as representing progress, the one true way forward, the most supposedly enlightened form of music, and so on. It would be much more rare to hear many within any faction questioning the status of new music as a whole, or the purpose of its institutions. Some who have done – not least various of the key figures viewed as ‘minimalist’ (Steve Reich, Philip Glass, John Adams, etc.) – have tended to operate to a large degree outside of these circles, while others holding to a neo-romantic or other related late tonal aesthetic have sought and sometimes found recognition within more mainstream performance circles.

In subsequent posts, I will consider wider issues to do with the institutionalisation of new music, the means by which it is legitimated (not least, in present times, by attachment to various political causes), and look more widely at the question of why new music and its practitioners enjoy a status in universities not always granted to other types of musicians and scholars. But here I want to consider some of the starkly opposed views from musicians scholars regarding the prestige of new music.

Milton Babbitt was one of the most articulate advocates of the benefits of new music composition in a university setting, allowing some degree of autonomy from audience indifference or hostility, or commercial pressures. This was outlined in his essay ‘The Composer as Specialist’ (1958), first published in High Fidelity, vol. 8, no. 2 (February 1958) to which editors (rather than Babbitt himself) gave the title ‘Who Cares if you Listen?’

Why should the layman be other than bored and puzzled by what he is unable to understand, music oranything else? It is only the translation of this boredom and puzzlement into resentment and denunciation that seems to me indefensible. After all, the public does have its own music, its ubiquitous music: music to eat by, to read by, to dance by, and to be impressed by. Why refuse to recognize the possibility that contemporary music has reached a stage long since attained by other forms of activity? The time has passed when the normally well-educated man without special preparation could understand the most advanced work in, for example, mathematics, philosophy, and physics. Advanced music, to the extent that it reflects the knowledge and originality of the informed composer, scarcely can be expected to appear more intelligible than these arts and sciences to the person whose musical education usually has been even less extensive than his background in other fields. But to this, a double-standard is invoked, with the words “music is music,” implying also that “music is just music.” Why not, then, equate the activities of the radio repairman with those of thetheoretical physicist, on the basis of the dictum that “physics is physics”? It is not difficult to find statements like the following, from the New York Times of September 8, 1957: “The scientific level of the conference is so high . . . that there are in the world only 120 mathematicians specializing in the field who could contribute.” Specialized music on the other hand, far from signifying “height” of musical level, has been charged with “decadence,” even as evidence of an insidious “conspiracy.”

I dare suggest that the composer would do himself and his music an immediate and eventual service by total, resolute, and voluntary withdrawal from this public world to one of private performance and electronic media, with its very real possibility of complete elimination of the public and social aspects of musical composition. By so doing, the separation between the domains would be defined beyond any possibility of confusion of categories, and the composer would be free to pursue a private life of professional achievement, as opposed to a public of unprofessional compromise and exhibitionism.

But how, it may be asked, will this serve to secure the means of survival for the composer and his music? One answer is that, after all, such a private life is what the university provides the scholar and the scientist. It is only proper that the university, which—significantly—has provided so many contemporary composers with their professional training and general education, should provide a home for the “complex,” “difficult,” and “problematical” in music. Indeed, the process has begun; and if it appears to proceed too slowly, I take consolation in the knowledge that in this respect, too, music seems to be in historically retarded parallel with now sacrosanct fields of endeavor. In E. T. Bell’s Men of Mathematics, we read: “In the eighteenth century the universities were not the principal centers of research in Europe. They might have become such sooner than they did but for the classical tradition and its understandable hostility to science. Mathematics was close enough to antiquity to be respectable, but physics, being more recent, was suspect. Further, a mathematician in a university of the time would have been expected to put much of his effort on elementary teaching; his research, if any, would have been an unprofitable luxury.” A simple substitution of “musical composition” for “research”, of “academic” for “classical”, of “music” for “physics,” and of “composer” for “mathematician,” provides a strikingly accurate picture of the current situation. And as long as the confusion I have described continues to exist, how can the university and its community assume other than that the composer welcomes and courts public competition with the historically certified products of the past, and the commercially certified products of the present?

Perhaps for the same reason, the various institutes of advanced research and the large majority of foundations have disregarded this music’s need for means of survival. I do not wish to appear to obscure the obvious differences between musical composition and scholarly research, although it can be contended that these differences are no more fundamental than the differences among the various fields of study.

Babbitt’s article demonstrates an unerring faith of a notion of musical ‘progress’, which he maps onto scientific research. But he does not ask what purpose the ‘complex’, ‘difficult’ and ‘problematical’ in music serves? It is not so difficult to demonstrate the wider impact and application of various types of science, but what is the equivalent for music? Over a hundred years on, Schoenberg’s atonal and dodecaphonic explorations have won only a modest following even amongst musicians, certainly compared to the more widespread valuing of music of Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Bartok, and others who were once viewed as members of avant-gardes. Some might cite the occasional use of atonal material in film or video games for particular effect, but this seems very modest in comparison to the claims made by Babbitt.

The polar opposite of Babbitt’s view can be found in feminist scholar Susan McClary’s essay ‘Terminal Prestige: The Case of Avant-Garde Music Composition’, Cultural Critique, No. 12 (Spring 1989), pp. 57-81, somewhat notorious in musicological circles. McClary considers the views of Arnold Schoenberg, Roger Sessions and Milton Babbitt on certain valorisations of ‘difficult’ music and its distance from mainstream audiences (though she has relatively little to say on the music itself):

Perhaps only with the twentieth-century avant-garde, however, has there been a music that has sought to secure prestige precisely by claiming to renounce all possible social functions and values [….]

This strange posture was not invented in the twentieth century, of course. It is but the reductio ad absurdum of the nineteenth-century notion that music ought to be an autonomous activity, insulated from the contamination of the outside social world. […]

In this century (especially following World War II), the “serious” composer has felt beleaguered both by the reified, infinitely repeated classical music repertory and also by the mass media that have provided the previously disenfranchised with modes of “writing” and distribution-namely recording, radio, and television. Thus even though Schoenberg, Boulez,and Babbitt differ enormously from each other in terms of socio-historical context and music style, they at least share the siege mentality that has given rise to the extreme position we have been tracing: they all regard the audience as an irrelevant annoyance whose approval signals artistic failure. [….]

By aligning his music with the intellectual elite-with what he identifies as the autonomous “private life” of scholarship and science (this at the height of the Cold War!) – Babbitt appeals to a separate economy that confers prestige, but that also (it must be added) confers financial support in the form of foundation grants and university professorships. [….]

Babbitt’s rhetoric has achieved its goal: most university music departments support resident composers (though many, including the composers in my own department, find the “Who Cares if You Listen” attitude objectionable); and the small amount of money earmarked by foundations for music commissions is reserved for the kind of “serious” music that Babbitt and his colleagues advocate.

I objected a good deal to McClary’s essay when I first read it some 20 years ago, but as time has gone on have come to felt that she is onto something important in her allusions to legitimation via alignment to scholarship and science, though the exaggerated statements about claims to autonomy are unsustainable, especially today, when so many composers seek to justify their work as much through allusions to society and politics as through its musical merits.

I mentioned earlier a review-article by Richard Taruskin which generated a lot of anger amongst new music practitioners. In a range of writings, including in the Oxford History of Western Music, Taruskin has been sharply critical about many claims made by those associated with modernism and the avant-garde to the mantle of history, and of the ways in which historiography and pedagogy has foregrounded work of this type and marginalised other varieties. Perhaps the most prominent expression of Taruskin’s view is that article which takes some CD reviews of the music of Donald Martino as its starting point, ‘How Talented Composers Become Useless’. This was first published in The New York Times on 10 March 1996, and reprinted in the collection The Danger of Music and Other Anti-Utopian Essays (Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2009), pp. 86-93. Like McClary, Taruskin grounds his critic in an attack on the position of Babbitt:

By comparing “serious” or “original” contemporary music to mathematics (and appropriating concepts like seriousness and originality to one kind of music was where the arrogance lay), Mr. Babbitt was saying, in effect, that such music was to be valued and judged not for the pleasure it gave but for the truth it contained. Truth, in music as in math, lay in accountability to basic principles of relatedness. In the case of math, these were axioms and theorems: basic truth assumptions and the proofs they enabled. In the case of music, truth lay in the relationship of all its details to a basic axiomatic premise called the twelve-tone row.

Again, Mr. Babbitt’s implied contempt and his claims of exclusivity apart, the point could be viewed as valid. Why not allow that there could be the musical equivalent of an audience of math professors? It was a harmless enough concept in itself—although when the math professors went on to claim funds and resources that would otherwise go to the maintenance of the “lay” repertory, it was clear that the concept did not really exist “in itself”; it inescapably impinged on social and economic concerns. Yet calling his work the equivalent of a math lecture did at least make the composer’s intentions and expectations clear. You could take them or leave them. […]

Mr. Martino’s piano music […] strives for conventional expressivity while trying to maintain all the privileged and prestigious truth claims of academic modernism. Because there is no structural connection between the expressive gestures and the twelve-tone harmonic language, the gestures are not supported by the musical content (the way they are in Schumann, for example, whose music Mr. Martino professes to admire and emulate). And while the persistent academic claim is that music like Mr. Martino’s is too complex and advanced for lay listeners to comprehend, in fact the expressive gestures, unsupported by the music’s syntax or semantics, are primitive and simplistic in the extreme. [….]

The reason it is still necessary to expose these hypocrisies, even after the vaunted “postmodern” demise of serialism, is that the old-fashioned modernist position still thrives in its old bastion, the academy. Composers like Mr. Martino are still miseducating their pupils just as he was miseducated himself, dooming them to uselessness. Critics and “theorists,” many of them similarly miseducated, are still propagandizing for Pointwise Periodic Homeomorphisms in the concert hall, offering their blandishments as consolation for the loss of a musical language and decrying the attempts of younger composers to find a new one.

Taruskin has gone on to be a leading advocate of the ‘Cold War’ view of avant-garde musical history, which maintains essentially that the institutionalisation and prestige of avant-garde music was a product of both an intellectual culture privileging quasi-scientific positivism, and was dominant in US universities, but also the conspiratorial view, which I maintain is utterly false on the basis of a lot of archival research, that the success of the Darmstadt Summer Schools for new music, and other aspects of new music in Europe, were the result of covert funding by the CIA. There is no evidence to substantiate this (unlike with some other art forms, from which information this conclusion has simply been inferred); as Ian Wellens in particular has shown, the primary CIA-funded organisation, the Congress for Cultural Freedom, had as its secretary general Nicolas Nabokov, who showed no real interest in serial and other avant-garde composition in the post-1945 era (as compared to his advocacy of the music of Stravinsky), and the events sponsored by the CCF are too exceptional and unrepresentative as to be defining in terms of the wider history. I will expand on this in a subsequent post.

A British figure who has delivered harsh critiques of new music and the prestige it entertains is Nicholas Cook, from whom I offer two citations. The first is from his ‘On Qualifying Relativism’, Musica Scientiae, vol. 5, issue 2 supplement (September 2001), pp. 167-189.

As Richard Toop (who works in Sydney but is closely associated with the European avanr-garde) points out, composition occupies very different roles in different countries. In North America it has been almost inextricably entangled with universities since the early days of Babbitt (whose “social contract”, as Herman Sabbe points out, “is with the academy”); the relationship is only a little less close in Britain, where composition is fully accepted as a form of research for purposes of institutional and national quality reviews. But in continental Europe, as Toop goes on to say, contemporary music revolves around festivals and radio stations; “One may be dealing with a heavily subsidized market place,” he adds, “but it’s a market place none the less.” Makis Solomos also raises the issue of subsidy, contrasting the subsidization of contemporary music in France with the situation in Britain (where the subsidies do exist, incidentally, but they go towards propping up the social rituals of the Royal Opera House rather than into contemporary music).

Solornos’s key observation, however, is that “en France, où les subventions existent, la musique contemporaine a un public”. It does in Britain and America too, of course, but there the audience has traditionally been one of contemporary music buffs, a niche within a niche. (One should recognize the potential for change not only through the cross-over musical styles of composers like Glass or Zorn, but also through the incorporation of contemporary music within educational and outreach programmes, which is why I said “traditionally”: all part of the crumbling of barriers to which I referred in my Foreword.) And when taking part in conferences or workshops in such countries as Holland, Belgium, and Germany I have always been struck by the centrality of contemporary composition within the definition of what “music” is and what an intelligent interest in the subject might mean: it is simply taken for granted that one has an interest in and commitment to contemporary music, in a way that it would never be in a similar situation in Britain or America. But it seems that the position of contemporary music is even more varied than this might suggest, to judge by the comments of Robert Walker (who writes from the University of New South Wales, Sydney): “it is indeed ironic”, he says,”that the academy can now include Beatles songs in analysis classes and research reports, but still not Berio’s vocal music”. And later he talks of Messiaen, Britten, Cage, and electronic music, and comments that “The music academy has shown comparatively scant interest in all this”. That surprised me, not only because new music was high on the agenda when I was teaching at Sydney University (though that was back in 1988), but also because music from Messiaen and Cage to Berio and beyond is well represented in the British academy, far beyond any possible measure of the music’s dissemination throughout society at large. It is popular music that is under-represented, resulting in a situation where the few PhDs in this area get quickly snapped up by university departments anxious to respond to the interests of their students.

The second is from ‘Writing on Music or Axes to Grind: road rage and musical community’, Music Education Research, vol. 5, no. 3 (November 2003), pp. 249-261.

Writers on contemporary ‘art’ music—what they often call ‘new music’—generally act as apologists, in the same sense as the earliest analysts did: writing in the early decades of the 19th century, these analysts’ basic purpose was to explain the coherence and hence the greatness of Beethoven’s music, despite its discontinuities and sudden irruptions and otherwise incoherent appearance (it would hardly be exaggeration to say that the whole genre of musical analysis developed as an act of advocacy for Beethoven). In the same way, writers on new music either argue that the music is aesthetically attractive even though it might appear otherwise on first acquaintance, or they argue that its aesthetic unattractiveness is integral to its cultural significance (and sometimes, just to make sure, they argue both). Their advocacy is prompted by the increasingly marginalised nature of the music—now even to some extent within academia—and this apologetic function is built into the genre: if you pick a book on new music off the shelf, you expect it to fulfil this role of advocacy, and again the few books that have attacked new music have appeared anomalous against this background. [….]

I’ve noticed that, when I go to conferences or similar events in continental Europe, people make the assumption that, because I’m interested in music, I must have an interest in and commitment to new music; that’s not an expectation about me in particular, but a taken-for-granted assumption about what it means to be seriously engaged in music. (In the UK or the USA, people make no such assumption.) And at least as far as the contributors to the Musicae Scientiae collection were concerned, this revolved not so much around the aesthetic properties of new music as its critical potential. In my book, I referred briefly to critical theory in general and Adorno in particular, as a way of introducing one of the main intellectual strands of the ‘New’ musicology of the 1990s, but I made no direct link between Adorno’s critique and new music. In her commentary, Anne Boissière (2001, p. 32) picked this up, asking why I didn’t discuss ‘the problem of contemporary music which resists consumption’: instead, she complained, I made music sound as if it was just another commodity, and in this way passed up the opportunity to offer ‘a critical analysis of consumer society’. In which case, she asked, ‘what point is there in making reference to Adorno?’: if one’s critique isn’t motivated by moral or political commitment, as Adorno’s was, then what is there to it but nihilism?

Actually, the argument Boissière is putting forward here, and which other contributors also reflected, has a long and rather peculiar history. It originates in the conservative critique of the modern world—the attack on capitalism and consumerism that developed throughout the German-speaking countries in the 19th century (where it was associated with the nostalgic values of an idealised rural past), and fed ultimately into the Nazi creed of ‘blood and soil’.

There are many ripostes to the views of McClary, Taruskin and Cook, just as there are to that of Babbitt, or those advocates of latter day composition-as-research who essentially adhere to his view. In subsequent posts I will consider some of these in more detail.

But for now, I just want to end with a plea for moderation. New music is a niche interest; this much appears very clear, and there is little evidence of such a situation changing. Can we accept this, and move away from both the unmediated and exaggerated claims for its centrality of Babbitt, the hatred and aggression towards dissenters, but also the types of denunciations of McClary, Taruskin and Cook, often clothed in ferocious political language (as with Cook’s attempts to link Boissière to the Nazis, to which I have alluded on here before)?

Those involved in new music who enjoy institutional prestige and economic wherewithal because of existing situations are unlikely to be sympathetic to any view which questions their status. Nor are those who jealously covet such a thing from different fields likely to have any sympathy towards them. Neither of these groups are likely to engage in mature scholarly debate. But such a debate ought to be possible without degenerating into polarised oppositions, including some of those presented above.

On Canons (and teaching Le Sacre du Printemps)

Posted: November 23, 2016 Filed under: Academia, History, Music - General, Musical Education, Musicology, New Music | Tags: albert roussel, aleksander glazunov, aleksander skyrabin, amy beach, antonio salieri, arnold schoenberg, arnold schoenerg, ars classica, beethoven, Birmingham, canons, carl stamitz, charles altieri, charles rosen, christine dysers, claude debussy, claude palisca, dead white european men, donald grout, earl hines, ethel smyth, fletcher handerson, franz liszt, frédéric chopin, friedrich engels, Friedrich Hölderlin, friedrich kalkbrenner, gaetano donizetti, giacomo puccini, gioachino rossini, giovanni pacini, great american songbook, gyorgy lukacs, hector berlioz, honore de balzac, igor stravinsky, j. peter burkholder, james reece europe, jelly roll morton, jelly roll mortone, jim samson, johannes brahms, john butt, john donne, joseph kerman, katherine bergeron, kid ory, king oliver, Le Sacre du Printemps, lil hardin armstrong, louis armstrong, max reger, Mikhail Glinka, mozart, musicology, nikolaiy roslavets, Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, paul whiteman, philip v. bohlman, pietro mascagni, saverio mercadante, second viennese school, serge rachmaninoff, simon zagorski-thomas, the original dixieland jazz band, Thomas Mann, vincenzo bellini, walter scott, walter wiora 7 CommentsI have been meaning for a while to post something detailed in my ‘Musicological Observations’ on the vexed subject of musical ‘canons’. A debate will take place tomorrow (Wednesday 23rd November, 2016) at City, University of London, on the subject, which I unfortunately have to miss, as I am away for a concert and conference in Lisbon. Having for a long period taught canonical (and also less canonical) music , and also lectured on the subject of canons in general, I naturally have plenty of thoughts and would have liked to contribute; I suggested most of the texts below (a list which is generally weighted in an anti-canonical direction, which is not my personal view). Nonetheless, the organiser of the debate, Christine Dysers, was very keen when I suggested I might blog something in advance of the debate, including some sceptical thoughts on the abstract. So here goes….

The abstract for this debate reads as follows:

“Dead White Men? Who Needs Musical Canons?”

What is the nature and purpose of musical canons? And what are the systems of authority that they sustain? Do they tend to act, as Jim Samson has suggested, ‘as an instrument of exclusion, one which legitimates and reinforces the identities and values of those who exercise cultural power’ (Samson 2001:7; from ‘Canon (iii)’, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie (2nd edn). Volume 5:6-7. London: Macmillan).

In this debate, speakers will explore notions of canonicity, particularly in relation to Euro-American art music. They will examine the reasons for the emergence of (largely composedly) canons and ask whether they still serve a useful purpose in the 21st Century.

Among other issues, speakers will consider the relations of power that underpin processes of canon-formation and ask whose ‘voices’ become marginalised, excluded or even forgotten. This will include, but not be restricted to, consideration of gender dimensions of canon-formation and how processes of inclusion/exclusion reflect underlying values, and ultimately ideas about the very ontology of ‘music’ itself. Such debates also raise questions about the role of canons in shaping categories of creative agency and hierarchies between ‘composer’, ‘performer’ and (often presented as rather passive) ‘listener’.

Suggested preparatory reading:

- Charles Altieri, ‘An Idea and Ideal of a Literary Canon’, Critical Inquiry 10/1 (Canons) (September 1983), pp. 37-60 – on literature, but one of the most notable essays which is more sympathetic to canons – https://www.jstor.org/stable/1343405?seq=1#fndtn-page_scan_tab_contents

- Katherine Bergeron and Philip V. Bohlman (eds), Disciplining Music: Musicology and Its Canons (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1992). In particular Bergeron, ‘Prologue: Disciplining Music’, pp. 1-9, and Randel, ‘The Canons in the Musicological Toolbox’, pp. 10-22.

- John Butt, ‘What is a ‘Musical Work’? Reflections on the origins of the ‘work concept’ in western art music’, in Concepts of Music and Copyright: How Music Perceives Itself and How Copyright Perceives Music, ed. Andreas Rahmatian (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015), pp. 1-22.

- Joseph Kerman, ‘A Few Canonic Variations’, Critical Inquiry 10/1 (Canons) (September 1983), pp. 107-125 – one of the first major essays on canon issues in a musical context, and still an extremely important text on the subject – https://www.jstor.org/stable/1343408?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Simon Zagorski-Thomas, ‘Dead White Composers’ – full text, link to recording, and a series of responses can be read here – https://ianpace.wordpress.com/2016/04/27/responses-to-simon-zagorski-thomass-talk-on-dead-white-composers

I find this abstract very deeply problematic in many ways. It is permeated throughout with a great many assumptions presented as if established facts, when they should actually be hypotheses for critical engagement, as if to try and bracket out any type of perspective which is at odds with those assumptions.

The first paragraph is almost a model of leading questions:

What is the nature and purpose of musical canons? And what are the systems of authority that they sustain? Do they tend to act, as Jim Samson has suggested, ‘as an instrument of exclusion, one which legitimates and reinforces the identities and values of those who exercise cultural power’ (Samson 2001:7; from ‘Canon (iii)’, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie (2nd edn). Volume 5:6-7. London: Macmillan).

Who has determined a priori that canons do indeed serve to sustain systems of authority? Whether indeed this is the case needs to be answered, and substantiated either way, rather than assumed. And, for that matter, how is a ‘canon’ defined (below I argue that fundamentally it is a necessary teaching tool)? Is it the set of composers who are regularly taught in particular institutions, or those who have sustained a regular listenership over a period of time, or those seen as epitomising particular strains of musical ‘progress’ through advanced and innovative compositional techniques, or indeed groups of musicians other than composers? Those questions may be said to fall within the issues of the ‘nature and purpose of musical canons’, but a less leading second question would be something along the lines of ‘Do canons serve to sustain other systems of authority, and if so, how?’

Samson is a subtle and nuanced thinker, who has written perceptively on (relatively) canonical composers such as Chopin and Liszt, and whose PhD dissertation, later published as a book, Music in Transition: A Study of Tonal Expansion and Atonality 1900-1920 (London: Dent, 1977) , focused on mostly canonical figures associated with the period of ‘transition’ at the beginning of the twentieth century. So I went back to the context of this quote (I do not have a hard copy of New Grove to hand, but see no reason to believe that the online version is different). Here is the actual quote:

The canon has been viewed increasingly as an instrument of exclusion, one which legitimates and reinforces the identities and values of those who exercise cultural power. In particular, challenges have issued from Marxist, feminist and post-colonial approaches to art, where it is argued that class, gender and race have been factors in the inclusion of some and the marginalization of others.

Samson does not ‘suggest’ this view, he points out that certain types of thinkers in particular have thought this – a view is being attributed to him which he is attributing to others. In this sense, the abstract misrepresents Samson’s balanced entry on the subject. I would draw attention to his second paragraph, which offers a wider (and global) perspective, and provides a good starting point for discussion:

Music sociologists such as Walter Wiora have demonstrated that certain differentiations and hierarchies are common to the musical cultures of virtually all social communities; in short, such concepts as Ars Nova, Ars Subtilior and Ars Classica are by no means unique to western European traditions. Perhaps the most extreme formulation of an Ars Classica would be the small handful of pieces comprising the traditional solo shakuhachi repertory of Japan, where the canon stands as an image of timeless perfection in sharp contrast to the contemporary world. But even in performance- and genre-orientated musical cultures such as those of sub-Saharan Africa, or the sub- and counter-cultures of North American and British teenagers since the 1960s, there has been a tendency to privilege particular repertories as canonic. Embedded in this privilege is a sense of the ahistorical, and essentially disinterested, qualities of these repertories, as against their more temporal, functional and contingent qualities. A canon, in other words, tends to promote the autonomy character, rather than the commodity character, of musical works. For some critics, the very existence of canons – their independence from changing fashions – is enough to demonstrate that aesthetic value can only be understood in an essentialist way, something we perceive intuitively, but (since it transcends conceptual thought) are unable to explain or even describe.

To present a range of different views on the role of canons might be more in the spirit of a debate.

Moving to the next paragraph:

In this debate, speakers will explore notions of canonicity, particularly in relation to Euro-American art music. They will examine the reasons for the emergence of (largely composedly) canons and ask whether they still serve a useful purpose in the 21st Century.

Phrases like ‘speakers will explore’ or ‘they will examine’ sound almost like diktats; more to the point, why single out Euro-American art music? Why not consider, say, the Great American Songbook, or some other repertoire of musical ‘standards’, which could be argued to serve an equally canonical purpose? Or how about looking at what I would argue is the canonical status of various popular musicians or bands – the Beatles, Madonna, and others – within popular music studies in higher education? Or at aspects of Asian musical traditions which some would argue are also canonical in the manner described in the Samson paragraph above?

Then the third paragraph:

Among other issues, speakers will consider the relations of power that underpin processes of canon-formation and ask whose ‘voices’ become marginalised, excluded or even forgotten. This will include, but not be restricted to, consideration of gender dimensions of canon-formation and how processes of inclusion/exclusion reflect underlying values, and ultimately ideas about the very ontology of ‘music’ itself. Such debates also raise questions about the role of canons in shaping categories of creative agency and hierarchies between ‘composer’, ‘performer’ and (often presented as rather passive) ‘listener’.

Once again we encounter many hypotheses presented as if established facts (and more diktats: ‘speakers will consider…’). Many of these loaded statements could be reframed as critical questions: for example, do canons indeed serve a function of marginalisation and exclusion?. I would ask whether, not how, processes of inclusion/exclusion reflect underlying values, whether canon-formation is a gendered process, and whether they shape the very categories of creative agency and hierarchies mentioned above. As I have recently criticised in some blurb accompanying a lavishly funded research project, this reads like an attempt to skip the difficult questions and present conclusions without doing the research first.

So, on to some thoughts of my own on the basic debate. Proper responses to the texts in questions (and others) will have to wait for a later post. I started thinking in a more sustained fashion about issues of canons first in the context of reading widely about the teaching of literature, then during my time as a Research Fellow at Southampton University, where the ‘new musicology’ was strong (I started off very sceptical, but was determined to familiarise myself with this work properly, then for a period believed that these musicologists were raising some important questions, even if I did not agree with many of their answers; nowadays I wonder if that engagement was a bit of waste of time and energy). There I taught a module on ‘Classical Music and Society’, which looked at various explicitly social/political paradigms for engaging with Western classical music, going back as far as Plato, and including a fair amount of Adorno, requiring students to actually read some of the original writings rather than simply rely upon secondary literature, though a critical approach was strongly urged (whilst basically sympathetic to the broad outlook of Adorno and other members of the Frankfurt School, I have many serious problems with this work, not least in terms of the reliance upon Freudian psychoanalysis). Some of the best essays which resulted were quite scathing about Adorno – though also some excellent ones were quite sympathetic.

Anyhow, in a lecture on Adorno’s views on modernism and mass culture, I contrasted the compositional technique and aesthetics on display in Igor Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps and in a range of works from Arnold Schoenberg’s ‘free atonal’ period. I did not expect many students to be familiar with Schoenberg, but was quite shocked when only a tiny number had at that stage heard Le Sacre. This made engagement with the issues Adorno raised all the harder.

I determined from that point that if I had the opportunity to teach a broad-based music history module, I wanted to ensure that the students taking it would at least have encountered this work – and numerous others. Not that I would demand any of them necessarily view it or other works positively (as Simon Zagorski-Thomas erroneously suggests is the primary purpose of musical education in Russell Group universities), but they had to have heard it properly in order to be able to develop any type of view.

Now Le Sacre remains a controversial work, about which I have many reservations, despite having played the two-piano/four-hand version a number of times with two duo partners, and listened to countless performances and recordings, and studied the work in some depth. But by so many criteria – in terms of lasting place in the repertoire and long-term popularity, influence on other composers, strong relationship to many other aesthetic and ideological currents, or revolutionising of musical language – Le Sacre is a vastly important work. Petrouchka runs it close (and possibly some later Stravinsky works as well). But I have yet to hear a convincing argument that, say, the contemporary works of Aleksander Glazunov or Nikolay Roslavets, or those of Max Reger, Albert Roussel, Pietro Mascagni after Cavalleria Rusticana, or Amy Beach, can be considered of equal significance by any measure (which is not to deny that their work can be of interest). But if comparing the work of Claude Debussy, Schoenberg, Aleksander Skryabin, Giacomo Puccini, Serge Rachmaninoff, and others, such an argument may be plausible. Or with respect to the work of leading jazz musicians – King Oliver, Kid Ory, Louis Armstrong, Lil Hardin Armstrong, The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, Jelly Roll Morton, James Reece Europe, Earl Hines, Fletcher Henderson and his orchestra, Paul Whiteman and his orchestra, Bix Beiderbecke, and many others active a decade after the premiere of Le Sacre. That is simply to allow for a diverse range of tendencies, all perceived to be of palpable importance, not to dissolve any judgement of value or indeed exclude the possibility of canon.

In short I want to argue for a reasonably broad and inclusive canon, if the term is viewed as a teaching tool. Anyone who has taught music history knows that the time available for teaching is finite, and so making choices of what to include, and what not, is inevitable (as with any approach to wider history). Students entering higher education in music often have only very limited exposure to a wider range of music, and need both encouragement and some direction in this respect; the only way to avoid making choices and establishing hierarchies is to give up on doing this. The moment one decides, when teaching Western classical music, to spend more time on Ludwig van Beethoven than Carl Stamitz, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart than Antonio Salieri, or Frédéric Chopin than Friedrich Kalkbrenner, one has established hierarchies of value.

When I got to teach my broad historical module – which covered the period 1848-2001 and I ran for six years – I attempted some breadth of approach (which made the module more than a little intense), incorporating various urban popular musics as much as classical traditions, including a substantial component on the histories of jazz, blues, gospel, rock ‘n’ roll, and many diverse popular traditions from the 1960s onwards, as well as much wider consideration of the possible historical, social and political dimensions of music-making and musical life during the period in question, which necessitated incorporation of a fair amount of wider history as well, working under the assumption that many students would not be that familiar with such events as the revolutions of 1848, or the shifting allegiances and nationalistic rivalries between the major powers in the period leading up to World War One. But this was still a course in music history, not a wider history course in which music was just one of many possible cultural tangents (the first time I taught it, I realised it was in danger of going in this direction, and I modified it accordingly in subsequent years), and so I needed to include a fair amount of actual music, music which could be listened to, not just read about, so that entailed compositions or recorded performances (the latter is obviously not an option for those teaching earlier musical periods, a very straightforward explanation for why musical composition, for which texts survive, has tended to be quite central in such teaching). So this necessitated some choices relating to inclusion/exclusion – one priority was not to give disproportionate attention to Austro-German nineteenth century compositional traditions, and consider more seriously those traditions existing in particular in France, Italy and Russia; another was, as mentioned before, to give proper space to non-‘classical’ traditions. There were numerous other criteria I attempted in this context, not least of which was to present plenty of music for which a link with the wider context was relatively easy to comprehend – but with hindsight, I think this was a very dubious criterion, and which artificially loaded the attempts to ask students to look critically at the relationship between music and history/society, not take some assumed relationship as a given. There are a great many positions which have been adopted by musicologists and music historians, from a staunch defence of autonomous musical development to a thoroughly deterministic view; I have my own convictions in this respect, but the point is not to preach these, but try to help students to be able to shape their own in an intelligent and well-informed manner.

Someone in another department commented to me quite recently of his astonishment that he encountered students who had never heard Brahms’s Second Symphony (said with some special emphasis as is characteristic of those with a strong grounding in a tradition, and for whom not knowing this would be like a literary student never having read or seen Macbeth). I replied that if I encountered a few students who had already heard a work like that before it was presented in a class, I would feel lucky. But that situation is now to be expected, and in my view musical higher education can do a lot worse than try to introduce students to a lot of music which lecturers, audiences, and many musicians over an extended period have found remarkable. Not in order to dictate to those students that they must feel the same way, but to expose them to work which has been found by a significant community to be of historical and aesthetic significance, and invite them to form their own view – which may be heretical.

So it is on this basis that I believe ‘canons’ are valid, indeed essential, teaching tools for musical history – whether dealing with histories of composers, performers or even institutions – if students are to be given some help and guidance in terms of studying sounding music. I refuse to accept the singular use of the term ‘the canon’, for this is not, and has never been, fixed when one considers different times and places. Mikhail Glinka and Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov occupy hallowed places within Russian musical life and history, so far as I can ascertain (not being a Russian speaker, so dependent upon secondary literature), but this view is only relatively rarely shared elsewhere. The canonical status of Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt has never been unambiguous, whilst that of Puccini and Rachmaninoff, as compared to the composers of the Second Viennese School, continues to be the source of healthy and robust debate. The place of Italian opera within wider canons of music from the eighteenth century onwards varies; I would also note, though, that within operatic history, Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini and Gaetano Donizetti are often canonised, but Giovanni Pacini and Saverio Mercadante are generally viewed as less central, to my mind an entirely natural decision. In terms of pre-Baroque or post-1945 repertoires, there is even less consensus. I for one find it very difficult to accept the particular choices of key works from the last few decades in the ninth edition of A History of Western Music by Donald Grout and Claude Palisca, revised by J. Peter Burkholder (New York: Norton, 2014).

I offer the following hypotheses (some of which I have no time to substantiate here) for critical discussion:

Aesthetics are more than a footnote to political ideologies, and canons reflect aesthetics in ways which cannot be reduced to the exercise of power.

There is not a singular canon, but a shifting body of musical compositions which are canonised to differing extents depending upon time and place.

Sometimes the process of canonisation is simply a reflection of what may not be a hugely controversial view – that not all music is equally worthy of sustained attention.

Canonical processes exist in many different fields of music, not just Euro-American art music in the form of compositions.

The most casual of listeners exhibit tastes and thus aesthetic priorities. These are not necessarily perceived as solely personal matters of no significance to anyone else, or else they would not be discussed with others.

It is impossible to teach any type of historical approach to musical composition and performance without including some examples, excluding others.

Many canonical decisions are made for expediency, and in order to provide a manageable but relatively broad picture of a time and/or place in musical history.

The broad-based attacks on canons, almost always focused exclusively on Western art music composition, are often a proxy for an attack on the teaching of this repertoire at all.

A very different view can be found in an essay of Philip V. Bohlman:

To the extent that musicologists concerned largely with the traditions of Western art music were content with a singular canon- any singular canon that took a European-American concert tradition as a given – they were excluding musics, peoples, and cultures. They were, in effect, using the process of disciplining to cover up the racism, colonialism, and sexism that underlie many of the singular canons of the West. They bought into these “-isms” just as surely as they coopted an “-ology.” Canons formed from “Great Men” and “Great Music” forged virtually unassailable categories of self and Other, one to discipline and reduce to singularity, the other to belittle and impugn. Canon was determined not so much by what it was as by what it was not. It was not the musics of women or people of color; it was not musics that belonged to other cultures and worldviews; it was not forms of expression that resisted authority or insisted that music could empower politics.

(Philip Bohlman, ‘Epilogue: Musics and Canons’, in Disciplining Music: Musicology and its Canons, edited Katherine Bergeron and Philip V. Bohlman (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1992), p. 198).

I can only characterise the above as a rant: musical canons are presented in language which might seem too extreme if describing Jimmy Savile or Slobodan Milosevic, and stops just short of indicting these in terms of complicity with widespread global dispossession and even genocide. But the paragraph is in no sense substantiated, and amounts to a series of rhetorical assertions. Furthermore, I would like to know more about how Bohlman thinks that music has indeed ’empowered politics’ in any significant number of cases, or why he thinks music is best rendered secondary to other uses, basically reiterating the rhetoric associated with Gebrauchsmusik in the 1920s and 1930s.

It is certainly true that Western classical music (and a fair amount of Western popular musics too) has at least until recently predominantly been made by white men, in part because the opportunities available to them did not exist to anything like the same extent for other groups. Complaints, for example, about lack of staging of operas by women composers make little sense without suggestions of works (other than Ethel Smyth’s The Wreckers and a small few others) which might feasibly be produced and would be acceptable in musical terms to a lot of existing opera audiences; relatively few women before recent decades were given the opportunities to write operas (which were rarely produced in isolation, but much more often in response to specific commissions). Only a shift to a greater amount of contemporary work in opera houses – which would create a new set of problems – opens up the possibility of a significantly increased representation of women composers. It is also hardly surprising that music produced in the Western world, at least in Europe, was only infrequently produced by ‘people of colour’ during times (basically, before the fall of many of the major European empires) when such people formed much smaller communities in European societies.

This is not to make light of the fact that opportunities for artistic participation have been strongly weighted in favour of certain groups in Western society over a long period (and, for that matter, in many non-Western societies as well). But the same was true of access to politics and government, the diplomatic service, banking, and very much else – the historical study of the figures who obtained and exercised power in these fields in Western societies before the twentieth century will be in large measure a history of white men. To arrive at a blanket decision on the workings of those fields on the basis of that information alone would be massively crude; the alternative is to spend time studying these histories before arriving at prognoses. To employ an ad hominem fallacy to dismiss vast bodies of creative work simply on account of the gender, class, ethnicity or other demographic factors relating to those who had the opportunities to produce, is myopic in the extreme, and smacks of a narrow politics of resentment. This is not a mistake that would have been made by Friedrich Engels, or the Hungarian Marxist intellectual György Lukács, both of whom wrote eloquently on the immense value of literary work by avowedly non-socialist thinkers such as Honore de Balzac, Sir Walter Scott, or Thomas Mann, in obviously political as well as aesthetic terms. The true believers in establishment values were those who – when nonetheless good writers who were prepared to allow their scenarios and characters to take on ‘lives of their own’- could, according to these thinkers, reveal more about the inner contradictions damaging these milieux, sometimes more so than some writers who identified with the left.

I would personally argue that the ubiquity of Anglo-American popular music (much of which interests me very much, and which as mentioned before I have taught extensively) is a far more hegemonic force in many societies than any sort of classical ‘canon’, which plays an increasingly marginal role in large numbers of people’s lives, especially in the face of cuts to and dumbing-down of musical education at many levels. As I argued (more than a little ironically!) in my response to Simon Zagorski-Thomas:

Personally, I can rarely go into a bar without being barraged by Japanese gagaku music, cannot go shopping without a constant stream of Stockhausen, Barraqué, mid-period Xenakis, or just sometimes examples of both French and Rumanian musique spectrale, piped over the loudspeakers, whilst when I jump into a taxi cab in most countries, I can be sure that there will be no escape from music of the Italian trecento. This is not to mention the cars going past blaring out the darkest Bach cantatas, or the endlessly predictable torrents of Weimar modernism which the builders will always put on the radio.

In a world which has recently witnessed the vote for Brexit, the election of Trump, and the growth of the far right in European politics, not to mention horrifying revelations of the abuse of children in a great many fields of life, a degree of economic collapse since the 2007 crash which does not appear to be recovering (especially in various Mediterranean countries), a wholly unholy civil war in Syria between the equally brutal forces of the Assad government and ISIS, the approaching 50th anniversary of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and subsequent dispossession and humiliation of the native population there, with no signs of change, ominous possibilities for catastrophic climate change, and so on, making such a big deal and assigning such loaded political associations to whether the teaching of music favours some types of music more than others seems a trivial, even narcissistic concern of musicians and musicologists. It may enable some to gain some political capital and concomitant advancement in the profession, but it is hard to see much more significance – indeed this may be a convenient substitute for any other political engagement, some of it directly related to academics’ professional lives, whether demonstrating against massive increases in student fees, or supporting and participating in industrial action in opposition to such things as the gender pay-gap. Perhaps energies could also be better spent elsewhere – such as playing a small but important role in trying to help some reasonable politicians get elected, rather than leaving the ground open to grotesque populist demagogues? This would be a much more laudable aim than fighting to ensure far fewer music students ever hear Le Sacre.

I wanted to end with some brilliant quotes from Charles Rosen, much better words than I could produce:

The essential paradox of a canon, however—and we need to emphasize this repeatedly—is that a tradition is often most successfully sustained by those who appear to be trying to attack or to destroy it. It was Wagner, Debussy, and Stravinsky who gave new life to the Western musical tradition while seeming to undermine its very foundations. As Proust wrote, “The great innovators are the only true classics and form a continuous series. The imitators of the classics, in their finest moments, only procure for us a pleasure of erudition and taste that has no great value.” Any canon of works or laws that forms the basis of a culture or a society is subject to continuous reinterpretation and to change, enlargements, and contractions, but to be effective it is evident that it must retain a sense of identity—it must, in fact, resist change and reinterpretation and yield to them reluctantly and with difficulty. A tradition’s sense of identity is dependent on the way it is transmitted, on what kind of access to it is made available to the members of the society concerned, and on whether the transmission makes the canon too rigid or too yielding.

(Charles Rosen, ‘Culture on the Market’ (2003), in Freedom and the Arts: Essays on Music and Literature (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2012), pp. 17-18).

Access to what are considered the great works of painting and sculpture is adequately provided by museums. They stand as a formidable barrier to those who would like to get rid of a canon, or radically alter its character (generally replacing dead white males with candidates selected by ideology, politics, or sexual preference). As I have said, a canon properly resists change, although, in the end, it must change if it is to exert a living influence. However, an abrupt and radical alteration is generally impossible to achieve: the old values spring immediately back into place once the new ideology’s back is turned. Introducing new figures into the canon is therefore, with few exceptions, a slow process, the additions generally reaching public acceptance only after decades of professional interest.

The example of two poets, John Donne and Friedrich Hölderlin, often said to have been discovered at the end of the nineteenth century after years of neglect, can show that the pathos of neglect and rediscovery is largely a myth. The present fame of Donne is popularly supposed to be owing to the influence of T. S. Eliot, but he was greatly admired by Coleridge and influenced Browning; and editions of his poetry were available throughout the nineteenth century. Perhaps the most influential academic critic of the time, George Saintsbury, wrote of Donne as “always possessing, in actual presence or near suggestion, a poetical quality that no English poet has ever surpassed.” The criticism of Eliot brought Donne to the attention of a larger public, but he had never lacked admirers. Hölderlin is said to have been rescued from complete obscurity at the same time as Donne by the interest of two great poets, Rainer Maria Rilke and Stefan George, but earlier Robert Schumann wrote music inspired by his work, and Brahms set his verses to music. The fame of both Donne and Hölderlin increased greatly at the opening of the twentieth century, but these additions to the canon were made possible by the earlier existence of a continuously sustained admiration.

The efficacy of a tradition, however, can be weakened by swamping it with a host of minor figures, and we have seen this happen in our time. The fashion for Baroque music has awakened the interest of recording companies and concert societies, and the novelty of an unknown figure has a brief commercial interest. A brilliant essay by Theodor Adorno mocked the way the taste for Baroque style reduced Bach to the status of Telemann, obliterated the difference between the extraordinary and the conventional. Concerts of music by Locatelli, Albinoni, or Graun are bearable only for those music lovers for whom period style is more important than quality.

(Ibid. pp. 20-21).

Finnissy Piano Works (7) and (8) – November 7th and 21st, Oxford

Posted: November 1, 2016 Filed under: Music - General, New Music | Tags: alexander scriabin, arnold schoenberg, beatles, erik satie, ferruccio busoni, Francisco de Vidales, georghi tutev, holywell music room, ian pace, johannes brahms, machaut, michael finnissy, olivier messiaen, samuel beckett, stanley stokes, tracey chadwell 2 Comments

[NEW: There will now be a new world premiere in the concert on Monday, November 21st, of the newly-composed Kleine Fjeldmelodien, dedicated to Ian Pace and Nigel McBride]

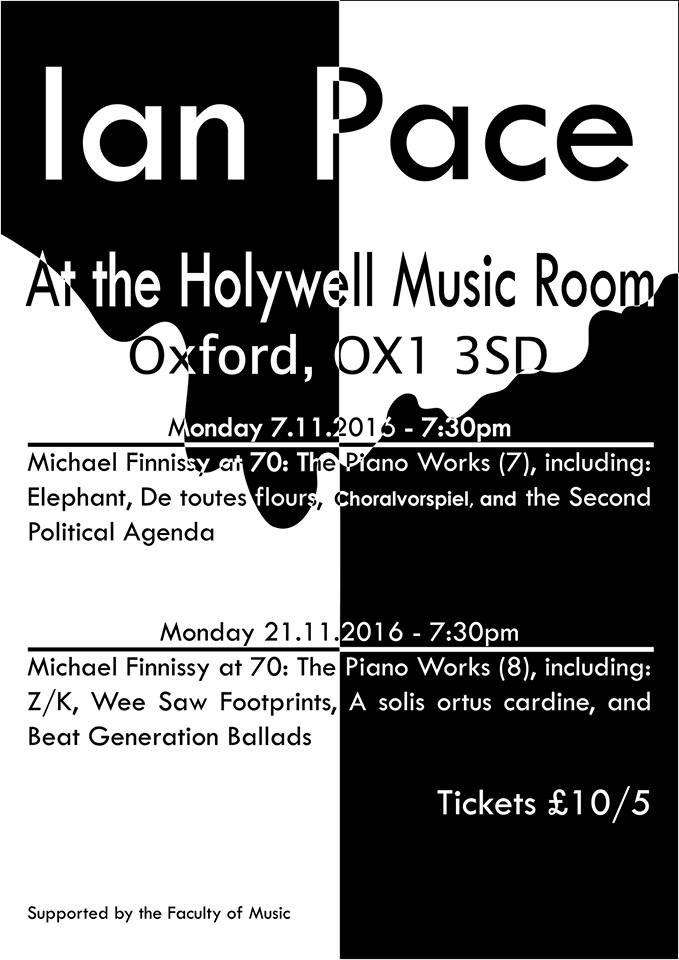

The seventh and eight concerts in my ongoing series of the complete piano works of Michael Finnissy will take place on Monday, November 7th, and Monday, November 21st, in the Holywell Music Room, Oxford. Both concerts will begin at 19:30. Tickets are £10, £5 concessions.

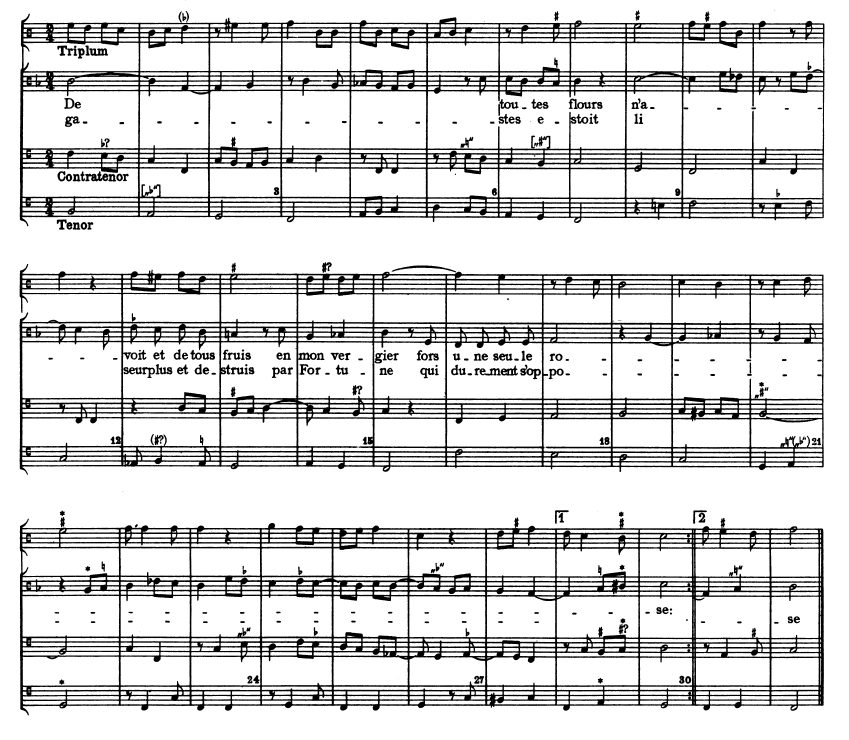

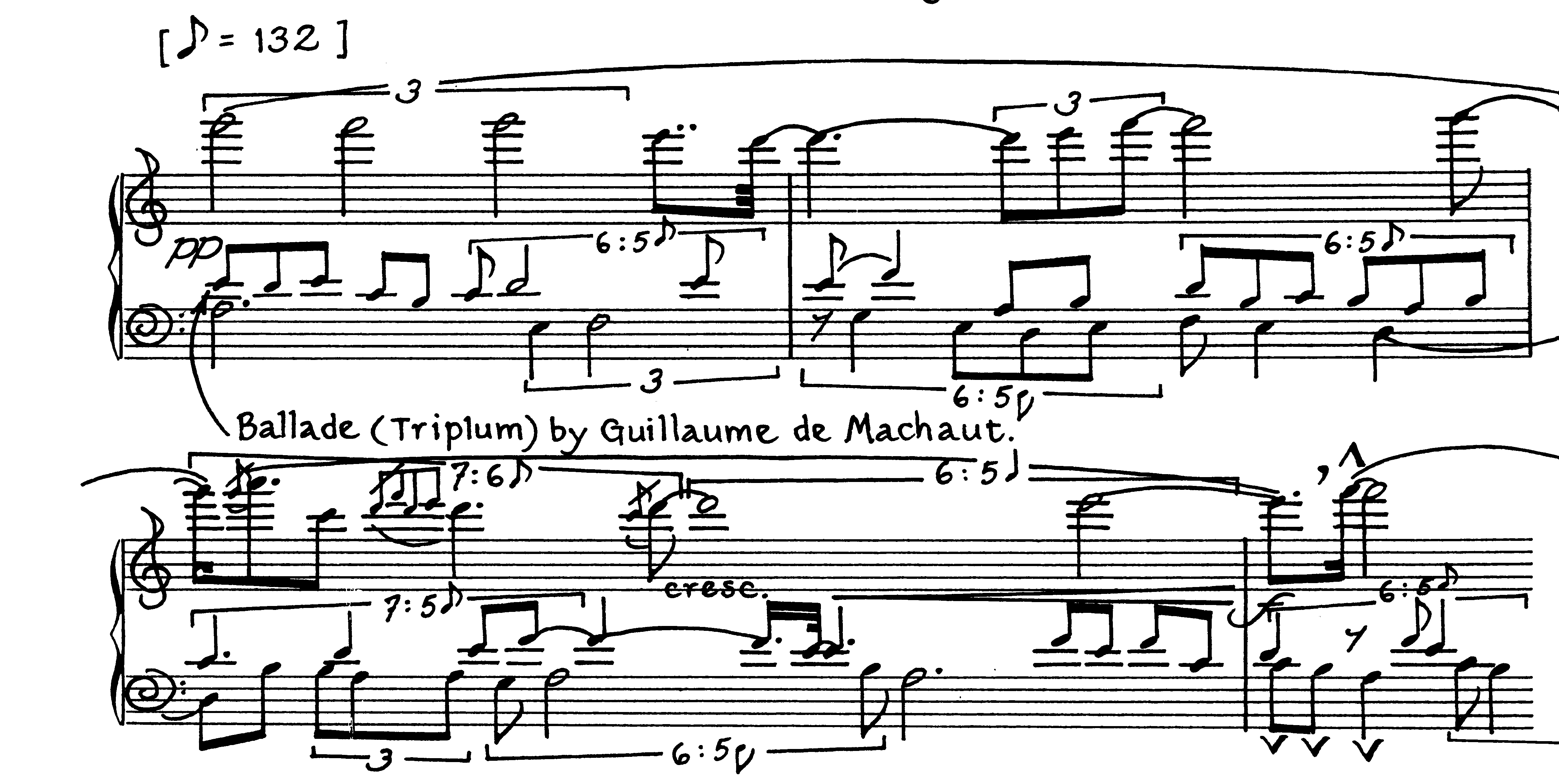

The first programme features a range of lesser-known works from the 1990s to the present day, including Finnissy’s unusual Machaut arrangement De toutes flours,of Francisco de Vidales’ villancico ‘Los que fueren de buen gusto’ in …desde que naçe, or his moving intimate tribute to soprano Tracey Chadwell, Tracey and Snowy in Köln. The much more extended Choralvorspiele (Koralforspill) is a series of fantastical post-Busoniesque chorale preludes sharing common material, an exercise in both compositional and pianistic virtuosity. The second half contains the second ever complete performance of the Second Political Agenda, three c. 20′ pieces embodying Finnissy’s extremely individual take on the music of Erik Satie, Arnold Schoenberg and Aleksander Skryabin.

The second programme features further tributes, to Satie again, to Oliver Messiaen in A solis ortus cardine, to Bulgarian composer Georghi Tutev, and the UK premiere of Finnissy’s Brahms-Lieder, not to mention his Beatles’ arrangement Two of Us, as well as some pieces written for children or elementary pianists in Wee Saw Footprints and Edward. The longer pieces in the programme include Enough, Finnissy’s response to Samuel Beckett’s short text Assez, and the monumental recent work Beat Generation Ballads.

Monday, November 7th, 2016, 19:30

Michael Finnissy at 70: The Piano Works (7)

Holywell Music Room, Holywell Street OX1 3SD

Elephant (1994)

Tracey and Snowy in Köln (1996)

The larger heart, the kindlier hand (1993)

…desde que naçe (1993)

De toutes flours (1990)

Cibavit eos (1991-92)

Zwei Deutsche mit Coda (2006)

Erscheinen ist der herrliche Tag (2003)

Choralvorspiele (Koralforspill) (2012)

***

Second Political Agenda (2000-8)

- ERIK SATIE like anyone else;

- Mit Arnold Schoenberg ;

- SKRYABIN in itself.

Guillaume de Machaut, De toutes flours

Finnissy, De toutes flours (1990)

Monday, November 21st, 2016, 19:30

Michael Finnissy at 70: The Piano Works (8)

Holywell Music Room, Holywell Street OX1 3SD

A solis ortus cardine (1992)

Stanley Stokes, East Street 1836 (1989-94)

Edward (2002)

Deux Airs de Geneviève de Brabant (Erik Satie) (2001)

Z/K (2012)

Brahms-Lieder (2015) (UK Premiere)

Enough (2001)

***

Wee Saw Footprints (1986-90)

Kleine Fjeldmelodien (2016) (World Premiere)

Lylyly li (1988-89)

Pimmel (1988-89)

Two of Us (1990)

Georghi Tutev (1996, rev. 2002)

***

Beat Generation Ballads (2013)

Meeting is pleasure, parting a grief (1996)

Finnissy, Stanley Stokes, East Street 1836 (1989-94)

Finnissy, Beat Generation Ballads (2013)

Yefim Golyshev, Arnold Schoenberg, and the Origins of Twelve-Tone Music

Posted: September 2, 2014 Filed under: Germany, Music - General, Musicology, New Music | Tags: arnold schoenberg, golyscheff, herbert eimert, josef matthias hauer, twelve-tone composition, yefim golyshev 7 CommentsMany pages of scholarship have been devoted to the origins of the twelve-tone technique, and whether Arnold Schoenberg can genuinely be considered the originator of the method. Groups of pitches which could be considered akin to twelve-tone rows have been located in various pre-twentieth century music, the most obvious example being the opening of Franz Liszt’s Faust Symphony. But this does not amount to the employment of a technique akin to that of Schoenberg. Since the pioneering research of Detlev Gojowy, it has been established for some time that a series of Russian composers arrived at their own use of twelve-tone complexes prior to Schoenberg. These would include the complexes found in Skryabin’s fragment Acte Préalable (1912), the second of Arthur Lourié’s Deux poemes, op. 8 (1912), the first of Nikolai Roslavets’ Two Compositions (1915), various works of Nicolas Obouhow from 1915 onwards such as Prières (1915) , and Ivan Vyschnegradsky in his La journee de l’existence (1916-17) [1] . These composers generally worked with post-Scriabinesque complexes which were expanded to include all twelve tones of the chromatic scale [2], quite distinct from the technique which Schoenberg would develop in the 1920s [3], and their work remained generally obscure and little-known outside of Russia at this point. Roslavets remained living in the Soviet Union after 1917, whilst Obouhow moved to Paris in 1918, and Lourié moved there in 1924 [4]. Alban Berg had used a harmony featuring all twelve chromatic pitches at the beginning of the third of his Altenberg-Lieder, op. 4 (1912),‘Über die Grenzen des All..’, op. 4, no. 3, then a twelve-note series in no. 5, ‘Hier ist Friede!’, as well as twelve-note themes in the Passacaglia, Act 1, Scene 4 (written before the end of 1919), and the Theme and Variations, Act 3, Scene 1, of Wozzeck (1914-22) [5], and Webern intuitively arrived at a way of organising the individual Sechs Bagatellen, op. 9 (1911) so that as a general rule, the piece would end after all twelve chromatic pitches had sounded, then began his ‘Gleich und Gleich’, op. 12, no. 4 with a statement of the twelve pitches with none repeated [6].

All of these developments demonstrate the extent to which the most radical varieties of chromaticism or pan-tonality were leading towards the establishment of twelve-note complexes (as would Schoenberg in 1914 in Die Jakobsleiter), but none had yet arrived at means for using sets of twelve chromatic notes in the forms of rows to provide fundamental structuring techniques. Three composers who did do this would have a definitive influence upon the future direction of dodecaphonic composition in Germany, each of who have been considered as rival contenders for having written the first twelve-tone work [7]: Yefim Golyshev (1897-1970), through the writings of Herbert Eimert (1897-1972), Josef Matthias Hauer (1883-1959), through the teachings of Hermann Heiß (1897-1966) and of course Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) through his own work and the music and teaching of numerous students.

The prodigious Odessa-born Golyshev moved to Berlin in 1909, his family fleeing anti-semitic pogroms [8]. Here he studied at the Stern’schen Konservatorium, and made the acquaintance of Busoni, who encouraged him in his musical work [9]; he may also have heard free atonal works of Schoenberg such as Pierrot Lunaire, which was first performed in the Berlin Choralion-Saal on October 16th, 1912 [10]. Golyshev remained living in the city through until 1933 [11].

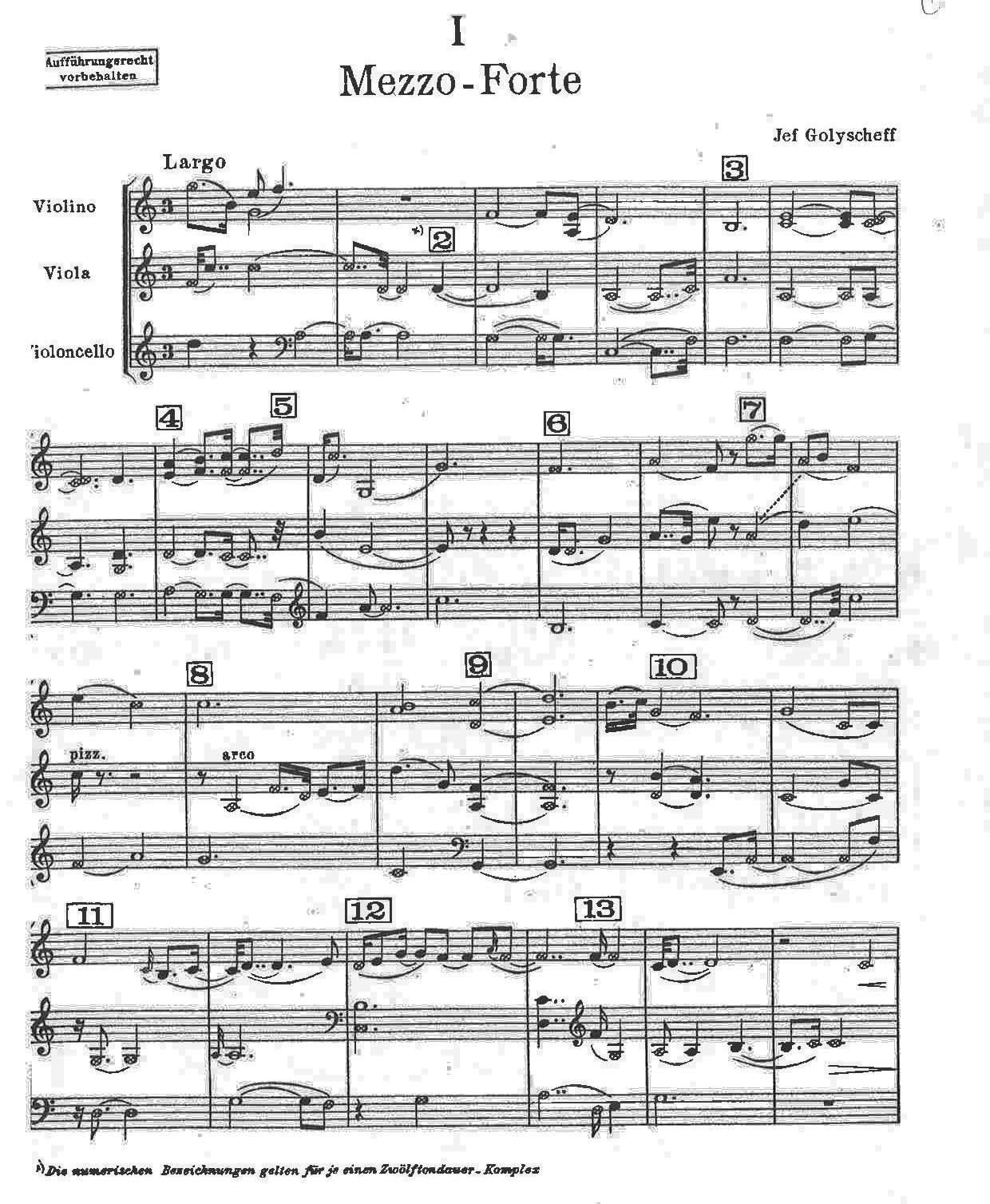

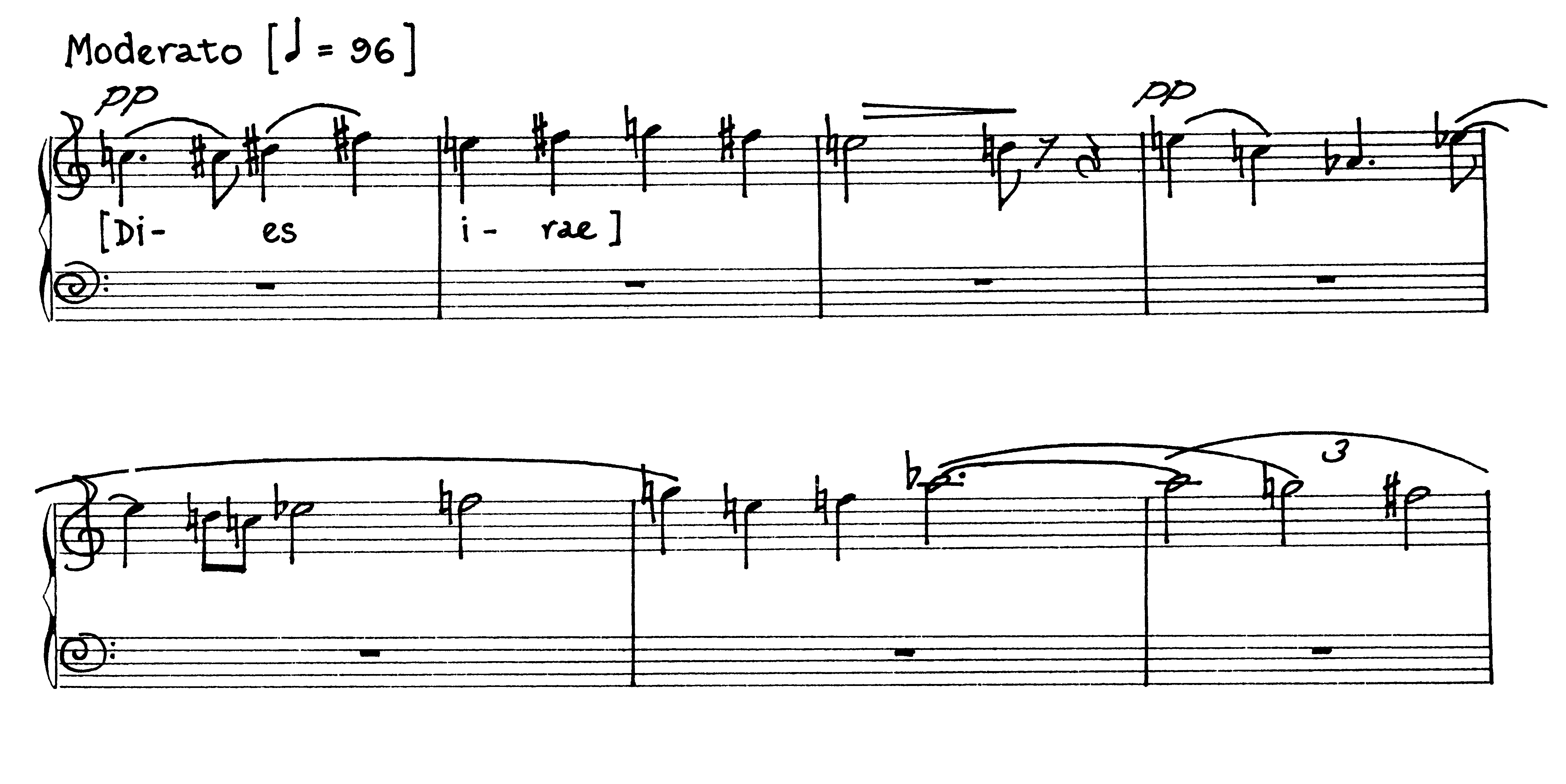

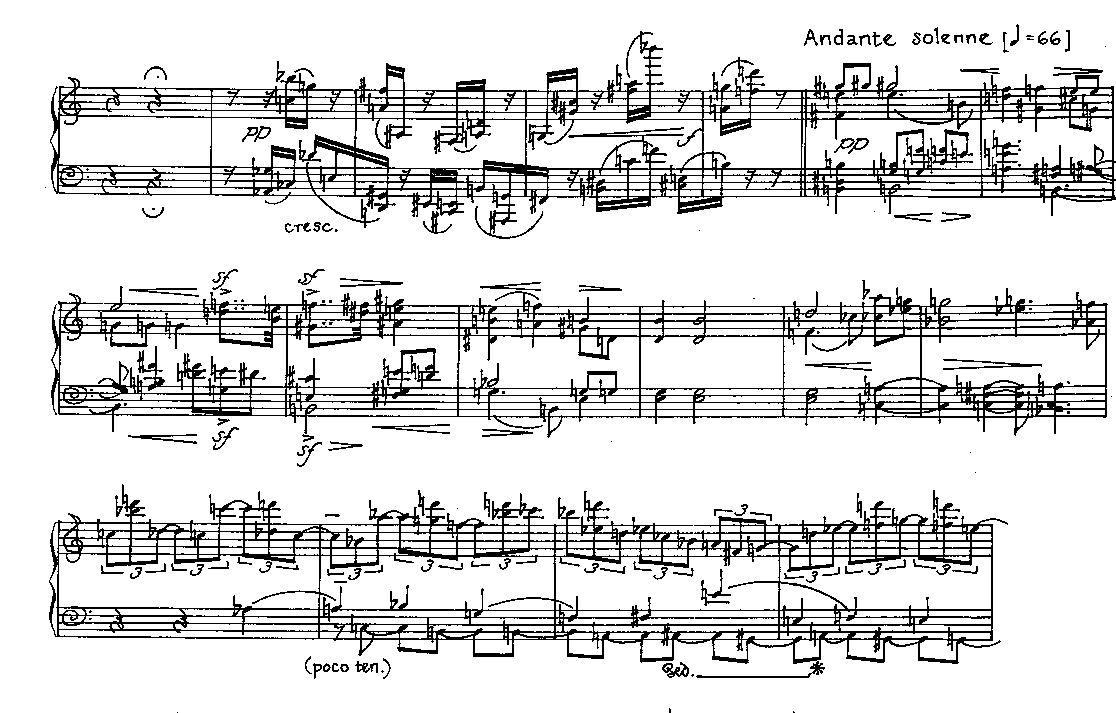

In 1914 (by his own account) Golyshev composed a five-movement dodecaphonic string trio (which was published in 1925 by Robert Lienau-Verlag as Zwölftondauer-Musik [12]), and in the same year began a string quartet which was intended for performance at the Gesellschaft für Neue Musik in Cologne in early 1923 [13]. A recording of this work is available here. The trio is structured around symmetrical patterns between movements as regards rhythms (so that the same figures are shared by the first and fifth, and the second and fourth), and uses twelve-note sets, which are clearly numbered in the score. In each section, all twelve notes are used, but not in a fixed order [14] (see below for the opening). Golyshev used a new notation to avoid conventional accidentals (distinct from that developed earlier by Busoni), by which a note with a cross inside the notehead indicates a sharp; others are natural [15].

A recording of the complete work can be heard here.

An orchestral work from 1919, Das eisige Lied, a symphonic poem lasting 75 minutes with songs, orchestral music and visual spectacle, was apparently also dodecaphonic, but is now lost [16]. During the war years Golyshev composed more and became friendly with Busoni, Richard Strauss, and Stravinsky, as well as Walter Gropius and other artists [17].

Golyshev’s father was a friend of Kandinsky’s, and the artist had persuaded inspired Golyshev to begin drawing prior to his move to Germany [18]. By the time of his Sinfonie aggregate, which was given its world premiere by the Berlin Philharmonic on February 21st, 1919 [19], Golyshev had become involved with the Dadaists, alongside Raoul Hausmann and Richard Huelsenbeck, and co-wrote a manifesto calling for a ‘brutal battle’ against ‘expressionism and the neoclassical culture as it is represented by Der Sturm’ [20]; his work featured prominently in the first Dada exhibitions [21]. He presented an Anti-Symphonie (Musikalische Kreisguillotine) as part of these exhibitions in April 1919, and went on to explore new musical instruments [22]; he also subsequently pursued a separate career as a chemist [23]. He would also become a member of the Novembergruppe at some point in the early 1920s, alongside the likes of Stuckenschmidt, Hans Tiessen, Max Butting, Philipp Jarnach, Kurt Weill, Wladimir Vogel, Hanns Eisler, Felix Petryek, Jascha Horenstein, George Antheil, and Stefan Wolpe [24].

One figure who was deeply interested in the work of Golyshev was the composer, critic and later producer at WDR, Herbert Eimert, who published his Atonale Musiklehre[25] in 1924, which Eimert himself claimed to be the first book of its kind in German [26]. This is a work whose highly mathematical tone, almost making a fetish of numerical patterns, differs very deeply from the presentations of Schoenberg in particular. Eimert also composed a twelve-tone string quartet for performance as part of his final examination. His conservative teacher, Franz Bölsche, was appalled by both of these, and intervened to have him expelled from the institution and the quartet removed from the programme [27]. In the Atonale Musiklehre, Eimert adopted Golyshev’s notational device throughout, and listed an unnamed Golyshev work from 1914 as the first example of twelve-tone music, then writing that Hauer had pursued pure atonality the following year [28]. Eimert at some point became a close friend of Golyshev, and owned several of his paintings which were destroyed during the war [29], but when they first met is unclear (likely before 1924), as Eimert’s memories were hazy, according to Helmut Kirchmeyer [30]. Eimert would go on to press the case for Golyshev being the first twelve-tone composer in various later writings [31].